REVIEW ARTICLE OPEN ACCESS

Ferroptosis and Notch Signaling Drive Tumor Progression and Therapeutic Vulnerability

Joanna Pancewicz1#, Wieslawa Niklinska1, Piotr M. Chodorowski2

Received 2025 Oct 2

Accepted 2025 Nov 23

Epub ahead of print: December 2025

Published in issue 2026 Feb 15

Correspondence: Joanna Pancewicz - Email: Joanna.Pancewicz@umb.edu.pl

The author’s information is available at the end of the article.

© 2026 The Author(s). Published by GCINC Press. Open Access licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. To view a copy: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Abstract

Ferroptosis is an iron-dependent form of regulated cell death characterized by unchecked lipid peroxidation and redox imbalance, which makes cancer cells vulnerable. The Notch signaling pathway is involved in cell survival, proliferation, differentiation, and helps cells adapt to metabolic and oxidative stress. Notch signaling intersects with ferroptosis through specific mechanisms: it modulates iron homeostasis by altering iron transport and storage proteins, influences lipid metabolism by regulating enzymes that modify membrane phospholipids, and affects antioxidant defenses by controlling the expression of genes such as SLC7A11 that regulate glutathione levels. As a result, Notch activity can sensitize cells to ferroptotic death by encouraging iron accumulation and lipid remodeling or confer resistance by increasing antioxidant capacity and reducing oxidative damage. In cancer, alterations in both ferroptosis and Notch signaling contribute to tumor initiation, progression, metastasis, and therapeutic resistance, in part through mechanistic interactions.

Recent studies report a link between ferroptosis and Notch signaling in several tumor types. However, this relationship likely varies by cancer type and experiment. Studying how these pathways connect could reveal new therapeutic targets, particularly in cancers that rely upon Notch-dependent metabolic programs or resist ferroptosis. Future work should address practical concerns. Selecting appropriate cellular targets, refining delivery methods, and understanding the tumor microenvironment will be important before demonstrating clinical benefits. Ultimately, more targeted ways to exploit the ferroptosis-Notch link may expand precision oncology tools. However, this remains under investigation and has not yet been approved as a therapy.

Keywords: Ferroptosis, Notch, Lipid Peroxidation, Cancer Therapeutic Targets, Metabolic Reprogramming, Immunogenic Cell Death (ICD), Iron metabolism, Precision oncology.

1. Introduction

Dixon and colleagues first reported on ferroptosis in 2012. They identified erastin, a molecule that induces a unique cell death in RAS-mutant cancer cells. This iron-dependent process involved severe lipid peroxidation but did not exhibit features of apoptosis or other forms of cell death (1). In the 2000s, research linked glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) to the breakdown of lipid peroxides. This showed a specific role for GPX4 (2). In 2003, Yant et al. found that GPX4 is vital for mouse embryonic development. GPX4-deficient embryos died from severe oxidative damage. This indicated a novel form of cell death caused by uncontrolled lipid peroxidation, although it had not yet been named (3).

Advances in genome-wide screening and chemical biology have further uncovered key regulators and features of ferroptosis, including LPCAT3 and ACSL4. Both enzymes alter the phospholipid composition of membranes, increasing the proportion of PUFAs and making lipids more susceptible to oxidation. LPCAT3 and ACSL4 define cell sensitivity to ferroptosis, linking lipid metabolism to cell death. Inhibitors of ferroptosis, such as ferrostatin-1 (Fer-1), liproxstatin-1, and vitamin E derivatives, have been used in vivo to link ferroptosis to diseases such as ischemia-reperfusion injury, neurodegeneration, and kidney failure. Notably, one study using adult mice lacking the GPX4 gene showed rapid, severe lipid peroxidation, kidney failure, and death. Administration of liproxstatin-1 prevented this damage, clearly demonstrating for the first time that ferroptosis directly causes tissue injury. These findings highlight that targeting ferroptosis may help treat certain diseases.

The study of Notch signaling began in fruit flies when scientists found a mutant with notched wings. This discovery demonstrated that Notch was required for proper development and survival, thereby establishing it as a master developmental regulator. Subsequent studies have shown that Notch is a conserved cell-cell signaling pathway. It regulates cell-type selection, boundary formation, and tissue health in many animals. Cloning Notch revealed it to be a large membrane receptor with multiple EGF-like repeats. Soon after, Delta was identified as a Notch ligand, demonstrating that Notch is activated by cell-cell contact. This clarified Notch’s developmental role and revealed it to be a juxtacrine signaling system. Additional studies explained the interactions between Notch and DSL ligands. High-resolution work detailed the EGF-like repeats and protein binding. This explained how ligand binding exposes the Notch regulatory region for proteolysis, releasing the active Notch domain. These findings established the modern model of Notch activation. Notch has also been shown to be a key regulator of stem cell function, tissue maintenance, and lineage decisions. Notch errors have been linked to cancer and developmental disorders. Genome-wide ChIP-seq mapped Notch’s transcription targets and revealed its complex networks. Results showed that Notch works with other pathways and chromatin factors to guide cell fates. This prompted searches for drugs to block the pathway, such as γ-secretase inhibitors (GSIs) and monoclonal antibodies. These are being tested for cancers and inherited disorders linked to Notch. Research also uncovered noncanonical Notch signaling, such as ligand-independent activation and metabolic roles. These advances show the broad role of Notch in cell communication and disease.

Several studies have begun to describe direct interactions between Notch signaling and cellular systems that influence ferroptosis. For instance, activating Notch1 can increase SLC7A11 expression, a key component of the system Xc⁻ transporter, thereby increasing cysteine uptake and supporting glutathione synthesis. These changes enhance a cell’s antioxidant defenses against ferroptosis. In this way, Notch1 maintains redox homeostasis and can reduce tumor cell sensitivity to ferroptotic triggers. Conversely, when Notch1 activity is reduced, SLC7A11 support diminishes, thereby lowering glutathione synthesis and increasing cell susceptibility to ferroptosis. Loss of Notch1 signaling thus contributes to glutathione depletion, lipid peroxide accumulation, and increased vulnerability to ferroptotic damage in multiple cancer models. These findings suggest that Notch pathway status regulates ferroptosis sensitivity primarily by modulating iron balance, antioxidant defense, and lipid composition, rather than through a single-step process. Here, we review studies on the interplay between ferroptosis and Notch signaling in cancer. We discuss why context matters, why pathways behave differently in tumors, and what questions remain before clinical use.

2. Ferroptosis: Mechanisms, Regulators, and Oncogenic Context

Ferroptosis is fundamentally distinct from other forms of regulated cell death because it is driven by iron-dependent lipid peroxidation, rather than caspase activation or mitochondrial dysfunction. A central mechanism underlying this process is intracellular iron overload. Elevated levels of ferrous iron (Fe²⁺) catalyze the Fenton reaction, in which Fe²⁺species, including hydroxyl radicals, are produced. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) can damage membrane components by oxidizing polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), often triggering a broader lipid peroxidation cascade that disrupts membrane stability. When these oxidized lipids rise beyond what the cell’s antioxidant defenses can manage, ferroptotic death becomes more likely. Unlike apoptosis or necroptosis, which engage distinct enzymatic programs, ferroptosis unfolds through iron-dependent oxidative reactions that reshape the cell’s metabolic and redox environment. In this setting, lipid peroxidation does not simply stop once initiated; oxidized phospholipids can generate additional reactive lipid species that continue to attack neighboring lipids, gradually undermining membrane integrity. Without sufficient buffering systems, particularly those involving GPX4 or glutathione metabolism, cells struggle to halt this feedback loop, leaving them vulnerable to a point of no return. Initially, ROS strips hydrogen atoms from PUFAs within membrane phospholipids, generating lipid radicals. These radicals rapidly react with molecular oxygen to form lipid peroxyl radicals, propagating oxidative damage throughout the membrane. As lipid peroxides accumulate, antioxidant defenses become overwhelmed. In particular, loss of GPX4 activity disables the cell’s ability to detoxify lipid peroxides, accelerating the peroxidation cascade. In parallel, impaired cystine uptake through SLC7A11 or SLC3A2 diminishes intracellular cysteine availability, limiting glutathione synthesis and further compromising the cell’s redox buffering capacity (22-24)

Beyond the well-characterized components of ferroptosis, some additional regulators also shape a cell's susceptibility to this form of death. One example is acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4 (ACSL4), which modifies membrane phospholipids by incorporating PUFA substrates. Cells that accumulate these lipid species tend to be more vulnerable to oxidative damage, thereby sensitizing them to peroxidation and promoting ferroptosis (25). Likewise, arachidonate 15-lipoxygenase (ALOX15) catalyzes the oxygenation of PUFA-containing phospholipids (PUFA-PL), thereby driving lipid peroxide accumulation (26-28). Conversely, two independent antioxidant systems counteract ferroptotic stress: ferroptosis suppressor protein 1 (FSP1), which regenerates coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10) to trap lipid radicals at the plasma membrane, and dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (DHODH), which performs a similar protective function within mitochondria (29-31). These parallel pathways underscore the complex multilayered control of lipid peroxidation beyond the classical GPX4-GSH axis.

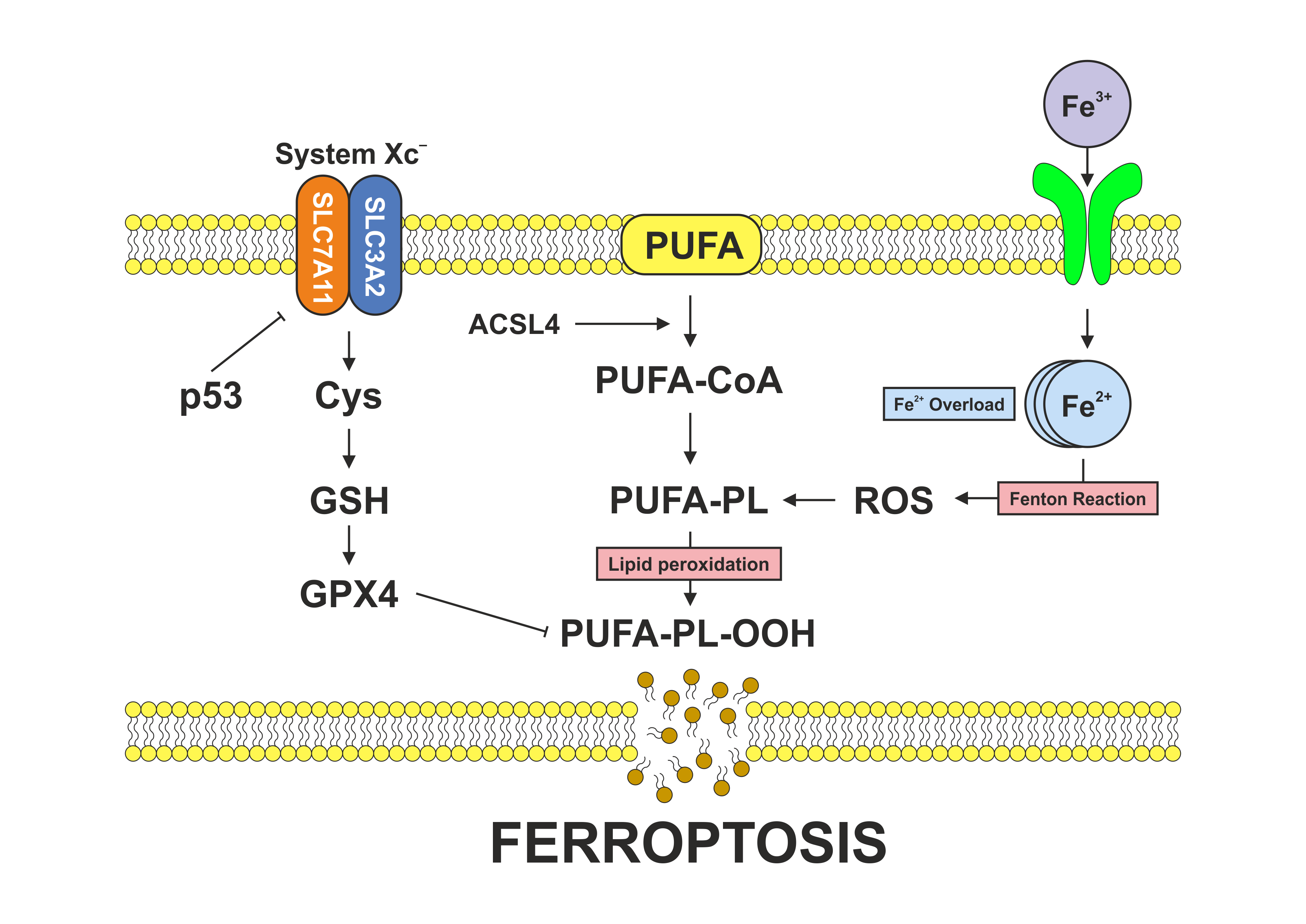

Ferroptosis is also modulated by the tumor suppressor p53, which exerts context-dependent effects on this cell‑death pathway. On one hand, p53 can promote ferroptosis by repressing SLC7A11 transcription, thereby reducing cystine import and limiting glutathione synthesis, conditions that weaken antioxidant defenses and sensitize cells to lipid peroxidation. On the other hand, p53 can also act as a negative regulator of ferroptosis under certain physiological or stress conditions. It achieves this by inducing p21, which slows cell-cycle progression and conserves intracellular redox capacity, or by reprogramming cellular metabolism to restrain excessive ROS production. These dual roles highlight p53 as a nuanced regulator that can either facilitate or suppress ferroptosis depending on cellular context, stress intensity, and metabolic state (32-34) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Mechanisms of ferroptosis. Schematic illustration showing the dual roles of the tumor suppressor p53 in ferroptotic cell death. p53 can promote ferroptosis by transcriptionally repressing SLC7A11, thereby limiting cystine uptake, depleting glutathione, weakening antioxidant defenses, and sensitizing cells to lipid peroxidation. Conversely, under specific physiological or stress conditions, p53 can suppress ferroptosis by inducing p21, which slows cell-cycle progression and preserves redox homeostasis, or by promoting metabolic reprogramming that limits excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS) production. Together, these opposing activities underscore p53 as a finely tuned regulator of ferroptosis whose net effect depends on cellular context, stress intensity, and metabolic state.

Moreover, beyond these canonical mechanisms, epigenetic and metabolic determinants play crucial roles in regulating ferroptosis sensitivity. Histone-modifying enzymes such as SETD1A, KDM5A, and HDAC3 reshape chromatin accessibility at ferroptosis-related loci, including GPX4, SLC7A11, and ACSL4, thereby influencing redox balance and therapy response (35,36). DNA methylation at the promoters of SLC7A11 and FSP1 confers ferroptosis resistance in hepatocellular and breast cancers, whereas demethylating agents can restore ferroptotic sensitivity (37).

Non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) have emerged as important post-transcriptional regulators of ferroptosis. Some microRNAs, miR-137 and miR-9, for instance, appear to limit ferroptotic activity by targeting SLC7A11, which influences cystine import and the availability of glutathione. Other ncRNAs behave differently. The long non-coding RNA LINC00336 has been reported to protect cells from ferroptosis, either by stabilizing GPX4 or by acting as a competing endogenous RNA that diverts microRNAs that promote ferroptotic signaling. Taken together, these examples illustrate how ncRNAs create an additional layer of regulation that can shift redox homeostasis and influence whether a cell undergoes ferroptotic death (38-40). These epigenetic and metabolic interactions integrate chromatin, transcriptional, and redox control to fine-tune ferroptotic thresholds, suggesting that combined targeting of epigenetic modulators and ferroptosis inducers may provide refined therapeutic opportunities (41).

3. Notch Signaling in Cancer: A Dual‑Role Developmental Pathway

Notch signaling is a highly conserved pathway that governs a wide range of developmental and homeostatic processes. Canonical Notch signaling is initiated when a Delta-like or Jagged ligand on one cell makes contact with a Notch receptor on an adjacent cell. This binding event leads to ligand endocytosis, which exerts mechanical force to expose the receptor’s negative regulatory region, thereby making it accessible to proteolytic cleavage. Processing by ADAM metalloproteases and the γ‑secretase complex releases the Notch intracellular domain (NICD), which translocates to the nucleus. NICD binds the transcription factor CSL/RBPJ and recruits co‑activators, such as Mastermind-like proteins, to increase the expression of canonical target genes that regulate differentiation, stemness, and tissue-specific programs.

Despite its conserved mechanism, the biological consequences of Notch activation are context-dependent. In some tissues, Notch functions as an oncogene, while in others it acts as a tumor suppressor. Oncogenic roles are well documented in human leukemias, where activating Notch1 mutations drive proliferation and block differentiation. Similar pro-tumorigenic effects have been observed in triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), certain lung cancers, and subsets of colorectal cancers (CRC), where Notch promotes survival and resistance to therapy. Conversely, in tissues such as the skin, liver, and myeloid compartment, Notch signaling limits excessive proliferation and supports differentiation, thereby acting as a barrier to transformation. Loss-of-function mutations within the Notch gene can contribute to tumorigenesis. This duality reflects the pathway’s reliance on cellular context, microenvironmental cues, and the transcriptional landscape in which NICD operates. As a result, therapeutic targeting of Notch requires careful consideration of tissue‑specificity to avoid unintended effects.

Although Notch signaling is best known for its role in directing cell-fate decisions, it also exerts broad metabolic effects across many cell types. Activation of the pathway can alter how cells manage energy production, reshaping metabolic circuits to meet the demands of growth or differentiation. Evidence from cancer studies indicates that Notch activity can push cells toward increased glycolysis, greater reliance on glutamine, and changes in mitochondrial behavior, adjustments that help sustain proliferation. The pathway also extends its influence to lipid metabolism, affecting the synthesis and remodeling of membrane phospholipids and potentially altering cellular responses to oxidative stress. Notch is also linked to antioxidant defenses; when active, it promotes the expression of genes that maintain redox balance, limit reactive oxygen species, and enable cells to cope with metabolic stress. When Notch activity is reduced, these protective functions are weakened, and cells become more susceptible to lipid peroxidation and, ultimately, ferroptotic death. Collectively, these observations suggest that Notch does not simply shape identity and lineage; it also helps coordinate the metabolic and redox landscape that determines a cell’s vulnerability to stress.

4. Crosstalk between ferroptosis and Notch signaling in cancer

Notch activity does not influence ferroptosis in isolation; it intersects with processes that shape a cell’s identity, energy use, and oxidative handling. When these elements align in particular ways, they can leave the cell markedly more or less sensitive to death triggered by lipid peroxidation. While these processes were once viewed as distinct, emerging studies demonstrate that they are tightly integrated through three shared biological frameworks: redox and antioxidant regulation, lipid metabolism and membrane vulnerability, and cellular stress signaling (42-44). Together, these domains establish a context-dependent “Notch-ferroptosis rheostat” that tunes ferroptotic susceptibility in response to metabolic needs, tumor microenvironment stresses, and oncogenic mutations.

Notch signaling modulates ferroptosis primarily by regulating lipid metabolism, antioxidant defenses, and iron homeostasis. By regulating enzymes such as ACSL4 and, indirectly, LPCAT3, Notch signaling can modulate the synthesis of PUFAs, key substrates for lipid peroxidation and ferroptotic cell death (45). Simultaneously, Notch regulates oxidative stress responses by modulating NRF2-dependent antioxidant genes, thereby fine-tuning the cellular redox balance and determining ferroptotic sensitivity (46,47).

Despite these common mechanisms, context-specific outcomes are evident across cancer types. For instance, in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), the Notch modulator NELL2 promotes ferroptosis by suppressing epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), increasing intracellular ROS, iron, and malondialdehyde (MDA), and reducing glutathione (GSH) (48). In contrast, in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), Notch3 activation protects against ferroptosis by maintaining the expression of GPX4 and PRDX6, key antioxidant enzymes, whereas Notch3 inhibition sensitizes tumor cells to ferroptosis inducers such as erastin (49). Similarly, in liver fibrosis, the IGF2BP3-Jag1-Notch axis stabilizes Notch signaling and elevates GPX4 expression, thereby suppressing ferroptosis (50).

When considered in context, the data imply that Notch does more than participate in isolated steps of ferroptosis; it also helps coordinate several processes that determine whether ferroptotic death will occur. By transcriptionally enhancing SLC7A11 and GPX4, Notch sustains glutathione synthesis and detoxifies lipid peroxides, opposing ferroptotic stress (51). It can also cooperate with Nrf2 to amplify antioxidant responses, thereby conferring a protective advantage in oxidative microenvironments, such as those found in tumors or fibrotic tissues. However, under stress or in specific genetic contexts, such as elevated mitochondrial ROS levels or TP53 mutations, Notch signaling may no longer suppress ferroptosis, leaving cancer cells more vulnerable to ferroptosis-inducing therapies.

This vulnerability is particularly relevant in hematologic malignancies, where ferroptosis-based interventions have shown considerable therapeutic promise. Studies in acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) have demonstrated that ferroptosis inducers, such as RSL3, erastin, and sulfasalazine, can significantly reduce leukemic cell burden in experimental models. Furthermore, selective inhibition of GPX4 has been shown to target acute myeloid leukemia (AML) preferentially, stem cells, while sparing normal hematopoietic stem cells, indicating that modulating the Notch-ferroptosis axis may open a unique therapeutic window for leukemia treatment (26,52).

Similar principles apply to solid tumors such as TNBC. Pharmacological targeting of SLC7A11 or GPX4 can re-sensitize TNBC cells to ferroptosis and suppress tumor progression, as shown in preclinical studies. TNBC represents an aggressive breast cancer subtype characterized by the absence of estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and HER2 expression, and is particularly susceptible to ferroptotic cell death. These tumors often exhibit elevated levels of PUFAs and have dysregulated iron metabolism, making them more vulnerable to lipid peroxidation. Moreover, SLC7A11, an essential component of the system Xc⁻ antiporter, is often overexpressed in breast cancer, where it enhances glutathione synthesis and supports GPX4 activity, thereby conferring resistance to ferroptosis (53-55).

Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) is one of the deadliest and most treatment-resistant types of brain tumors. GBM cells frequently exhibit elevated iron absorption and altered metabolism, rendering them more susceptible to ferroptosis under stress. Notably, Notch1 has been shown to suppress SLC7A11 expression, thereby weakening cystine import and sensitizing cells to ferroptotic death. These findings suggest that ferroptosis-inducing agents may be especially effective in GBM tumors with impaired Notch signaling or diminished antioxidant capacity. This vulnerability is even more pronounced in glioblastoma stem-like cells (GSCs), which depend heavily on robust antioxidant systems, including GPX4 and FSP1, to maintain survival and stemness. When these protective pathways are disrupted, GSCs undergo ferroptosis, resulting in reduced self-renewal and impaired tumor-initiating potential (56-59).

Ferroptosis has been shown to exert a tumor-suppressing effect in colorectal cancer (CRC), and compounds such as genistein or sulfasalazine can trigger ferroptosis by downregulating SLC7A11 and GPX4 expression (60,61). However, many CRC cells exhibit inherent resistance to ferroptosis, driven in part by activation of antioxidant pathways, including the NRF2-HO1 axis, and by metabolic adaptations that reshape lipid composition. Given that Notch signaling can enhance oxidative stress resistance and promote fatty acid oxidation, it is reasonable to speculate that Notch activation may contribute to ferroptosis resistance in CRC. Supporting this idea, research in other tumor types has shown that Notch3-mediated fatty acid oxidation reduces lipid peroxide accumulation, indicating that a similar mechanism might be involved in colorectal tumors (62).

Another example is prostate cancer (PCa) driven by hormones, distinguished by its metabolic adaptability, redox changes, and resistance to treatment. High-grade and castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) frequently exhibits elevated Notch signaling, driven predominantly by the Notch1 and Notch3 receptors. Jagged1/2 and Delta-like ligands trigger this signaling pathway, which results in the transcriptional upregulation of Hes1, Hey1, and Myc. These factors collectively promote the EMT and stress-tolerant survival (63). In parallel, the androgen receptor (AR) signaling pathway controls genes involved in glutathione homeostasis and lipid metabolism, which, in turn, directly affect ferroptotic sensitivity. Notably, AR has been reported to transcriptionally repress ACSL4 in prostate cancer, leading to reduced synthesis of PUFA-CoA and the ensuing PUFA-phospholipids, such as PE (phosphatidylethanolamine), which are substrates for lipid peroxidation in ferroptosis (64).

Table 1. Role of Ferroptosis and Notch Signaling in Selected Cancer Types.

| Cancer Type | Ferroptosis Roles | Notch Roles |

|---|---|---|

| Breast Cancer | Promotes metastasis through mechanisms like PUFAs accumulation and resistance to ferroptosis-inducing conditions. Suppressing tumor growth and improving the effectiveness of conventional therapies, while also being a potential target for new treatments | Oncogenic |

| Glioblastoma | Influence proliferation, invasion, and the tumor's immunosuppressive microenvironment. | Oncogenic |

| Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia | Facilitates metastasis by providing metastatic cells with resistance to ferroptosis, partly through the accumulation of fatty acids and glutathione. | Oncogenic |

| Acute Myeloid Leukemia | Involved in the development and progression of the disease. | Context dependent |

| Colorectal Cancer | Can contribute to progression and metastasis. The expression of ferroptosis-related genes correlates with chemosensitivity to certain drugs, suggesting a role in resistance mechanisms. | Context dependent |

| Hepatocellular Carcinoma | Can be a therapeutic target, with some drugs like sorafenib inducing cell death via ferroptosis. | Oncogene (primarily) |

| Gynecological Cancers | Contributes to tumor progression, invasion, and metastasis through the regulation of lipid metabolism and oxidative stress | Context dependent |

| Prostate Cancer | Influences invasion and migration through the regulation of lipid metabolism and ferroptosis key regulators like ACSL4 | Context dependent |

5. The Role of Ferroptotic Cells in Activating Antitumor Immunity

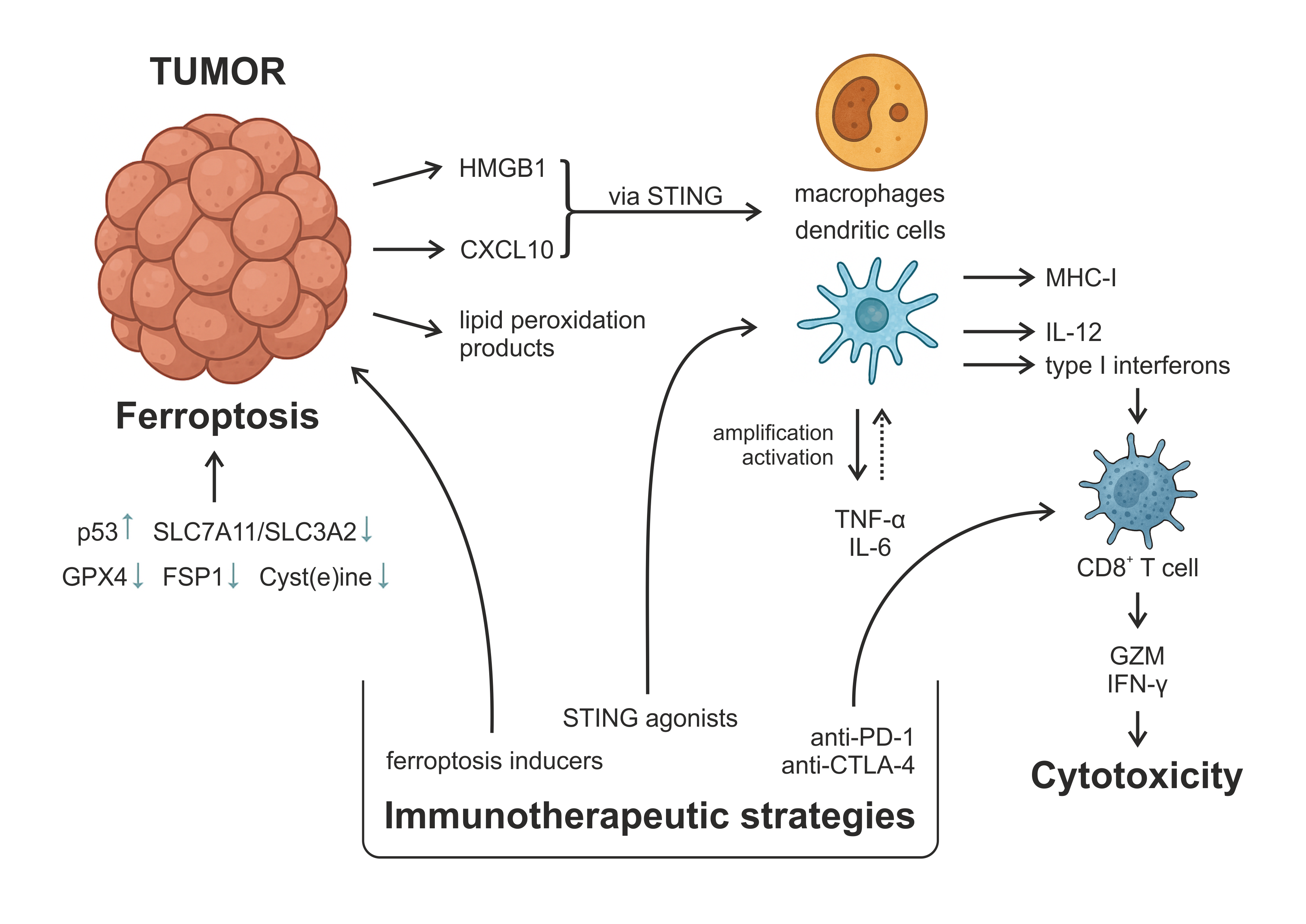

Ferroptosis, in addition to its innate ability to suppress tumors, has been recognized as a key modulator of the immune response within the TME (Figure 2) (65,66). Unlike apoptosis, which is generally immunologically silent, ferroptotic cell death can exhibit immunogenic features under specific conditions. The interplay between ferroptotic tumor cells and immune components underscores their dual roles as both a cell death mechanism and a potential trigger of antitumor immunity (Table 2) (67,68).

A hallmark of immunogenic cell death (ICD) is the release of damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), which serve as danger signals. Ferroptotic cells release various DAMPs, including ATP, HMGB1, and calreticulin, which promote dendritic cell (DC) recruitment and maturation, enhance cross-presentation of tumor antigens to CD8⁺ T cells, and elicit robust antitumor responses (69-71). Conversely, CD8⁺ T cells can actively induce ferroptosis in tumor cells. Interferon-γ (IFN-γ) released by activated T cells downregulates SLC3A2 and SLC7A11, key components of the cystine/glutamate antiporter system Xc⁻, thereby impairing glutathione synthesis and increasing susceptibility to ferroptosis (72).

Ferroptosis is also characterized by extensive lipid peroxidation, producing oxidized phospholipids and 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE), which activate DCs via TLR4-STING signaling, stimulate type I interferon secretion, and promote CD8⁺ T-cell activation (73). These lipid peroxidation products further modulate immune cell behavior, serving as chemoattractants or triggers for innate immune responses. Notably, lipid peroxide accumulation in the TME can influence macrophage recruitment and polarization, with pro- or antitumor outcomes depending on tumor type and context (74-76). From a therapeutic perspective, inducing ferroptosis offers the dual benefit of direct tumor cell killing and enhancement of immune-mediated clearance. Preclinical studies combining ferroptosis inducers with immune checkpoint inhibitors, such as anti-PD-1 or anti-CTLA-4 antibodies, have demonstrated promising results in overcoming immune resistance in tumors with low inherent immunogenicity (77,78).

Table 2. Immune processes influenced by ferroptosis in the tumor context.

| Key Process | Mechanism | Immune Cell Type | Effect on Immunity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Release of DAMPs | ATP, HMGB1, calreticulin released from ferroptotic cells | Dendritic cells | Promotes DC maturation and antigen presentation |

| Lipid Peroxidation Products | Generation of oxidized phospholipids, 4-HNE | Macrophages | Context-dependent activation or suppression |

| IFN-γ–mediated ferroptosis | IFN-γ from CD8⁺ T cells downregulates system Xc⁻ (SLC7A11/SLC3A2), sensitizing tumor cells | CD8⁺ T cells | Enhances tumor cell ferroptosis and immune clearance |

| Antigen cross-presentation | Mature DCs present tumor antigens released from ferroptotic cells | CD8⁺ T cells | Stimulates cytotoxic T cell activation |

| Temporal context | Early ferroptosis promotes immunity; late-stage can induce immunosuppression | Multiple | Determines overall immune outcome |

| Therapeutic implications | Combination of ferroptosis inducers with immune checkpoint inhibitors | Immunotherapy strategies | Potential synergistic antitumor effects |

Figure 2. The Role of ferroptotic cell death in triggering antitumor immunity. Figure 2 illustrates the immunogenic cascade initiated by ferroptotic tumor cells and its implications for antitumor immunity and therapeutic intervention. Ferroptosis is induced through suppression of antioxidant defenses (e.g., GPX4, FSP1) and cyst(e)ine metabolism, often regulated by p53 and SLC7A11/SLC3A2 transporters. Ferroptotic cells release damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), such as HMGB1 and lipid peroxidation products, as well as chemokines, including CXCL10. These DAMPs engage pattern-recognition pathways, such as TLR4-dependent signaling and, in some contexts, cGAS-STING activation by oxidized nucleic acids, thereby promoting DC maturation and improving antigen processing and MHC-I cross-presentation. Mature DCs produce cytokines, including IL-12 and type I interferons, that support the priming of cytotoxic CD8⁺ T cells. Activated CD8⁺ T cells secrete granzyme B and IFN-γ, amplifying antitumor cytotoxicity and promoting further ferroptotic stress within tumor cells. Inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α and IL-6, contribute to the recruitment and activation of additional immune cells within the tumor microenvironment. Therapeutically, ferroptosis inducers can enhance tumor immunogenicity and synergize with immunotherapies, including immune checkpoint blockade (anti-PD-1, anti-CTLA-4) and STING agonists, to overcome resistance and improve tumor eradication.

6. Therapeutic Implications of Targeting the Notch-Ferroptosis Axis

Targeting the Notch-ferroptosis axis represents a promising therapeutic approach. Combining Notch inhibitors with ferroptosis inducers may yield synergistic antitumor effects in cancers where Notch signaling suppresses ferroptosis and promotes tumor survival. Given the high activity of Notch3- or Jag1-mediated pathways in NSCLC and liver tumors, this strategy may be particularly effective in these malignancies.

6.1 Targeting Ferroptosis

Some molecular markers serve as indicators of ferroptosis sensitivity in cancer. Elevated expression of SLC7A11 (xCT) is a widely recognized biomarker, as it reflects enhanced cystine uptake and glutathione synthesis, both of which suppress lipid peroxidation and promote ferroptosis resistance. High GPX4 protein levels indicate strong antioxidant capacity that protects cells against phospholipid oxidation. In contrast, increased expression of ACSL4 and LPCAT3 is associated with increased ferroptotic vulnerability, as these enzymes drive the incorporation of PUFAs into membrane phospholipids, the substrates required for lethal lipid peroxidation. Additionally, the activity of FSP1 and genes involved in CoQ10 metabolism provides an alternative, GPX4-independent defense system; reduced expression of these components often correlates with increased ferroptosis sensitivity. Collectively, these biomarkers help define the ferroptotic landscape of tumor cells and guide the development of targeted therapeutic strategies.

Building on these insights, several therapeutic approaches aim to exploit ferroptosis in cancer treatment. GPX4 is a key regulator of ferroptosis, and its inhibition has emerged as a potential anticancer strategy. GPX4 inhibitors, including (1S,3R)-RSL3, FINO2, and FSP1, are being evaluated preclinically for their ability to induce ferroptosis in tumor cells, particularly those resistant to conventional therapies (79,80). System Xc⁻, a cystine/glutamate antiporter, maintains intracellular glutathione levels and protects against ferroptosis. Inhibitors such as sulfasalazine and erastin disrupt this system, depleting glutathione and sensitizing cancer cells to ferroptosis. Their efficacy is being assessed in clinical trials across several cancer types, including glioblastoma, NSCLC, and other malignancies (81,82). Combination strategies are under active investigation, with ferroptosis inducers being paired with immune checkpoint inhibitors or standard chemotherapies to enhance antitumor efficacy. For example, GPX4 inhibitors combined with PD-1/PD-L1 blockade have shown promising results in preclinical models of TNBC (83,84).

6.2 Targeting Notch Signaling

Several molecular indicators can be used to assess the functional status of the Notch signaling pathway in cancer cells. Expression levels of the Notch1, Notch2, and Notch3 receptors serve as primary biomarkers, reflecting the pathway’s activation potential at the cell surface. Similarly, the abundance of Jagged and Delta-like (DLL) ligands provides insight into upstream signaling cues within the TME. Downstream, transcriptional targets such as Hes1 and Hey1 are readouts of canonical Notch pathway activation. In addition, mutations in Notch genes, whether activating or inactivating, can alter pathway dynamics and are increasingly used as clinically relevant biomarkers that influence tumor behavior and therapeutic response. Collectively, these markers help define the Notch signaling landscape and guide intervention strategies.

γ-Secretase inhibitors (GSIs), such as nirogacestat (Ogsiveo), block Notch signaling by preventing the cleavage of Notch receptors. These inhibitors have shown efficacy in treating desmoid tumors and are being tested in other malignancies (85). Since Notch signaling is essential for maintaining the balance between absorptive and secretory cells in the intestinal epithelium, the use of GSI is frequently associated with side effects. These can be alleviated by intermittent dosing schedules, lower doses with targeted combinations, or more selective Notch-sparing approaches (e.g., monoclonal antibodies, DLL4 inhibitors, or ADAM inhibitors). Monoclonal antibodies targeting Notch receptors or their ligands are used to prevent tumor growth and overcome resistance mechanisms driven by dysregulated Notch signaling. For instance, early-phase clinical trials for pancreatic and small-cell lung malignancies have assessed the anti-Notch2/3 antibody tarextumab (OMP-59R5). Brontictuzumab (OMP-52M51), which targets Notch1, has also shown early anticancer activity in hematologic malignancies and solid cancers that have relapsed or are resistant. Furthermore, phase I trials have been conducted in solid tumors, such as colorectal and pancreatic cancer, using demcizumab (OMP-21M18), an antibody targeting the Notch ligand DLL4 (86-88).

6.3 Synthetic Lethality and Drug Resistance

Tumor cells can acquire resistance to ferroptosis through multiple mechanisms, including upregulation of antioxidant pathways (e.g., GPX4, FSP1), alterations in lipid metabolism, and activation of survival signaling networks. These adaptive responses limit the efficacy of ferroptosis-based therapies and represent a significant barrier to clinical translation. Dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (DHODH), a key mitochondrial enzyme, has been shown to protect cancer cells from ferroptosis by maintaining mitochondrial redox homeostasis. Pharmacological inhibition of DHODH, either alone or in combination with GPX4 inhibitors, has emerged as a potentially important strategy to overcome ferroptosis resistance in chemoresistant tumors (89,90).

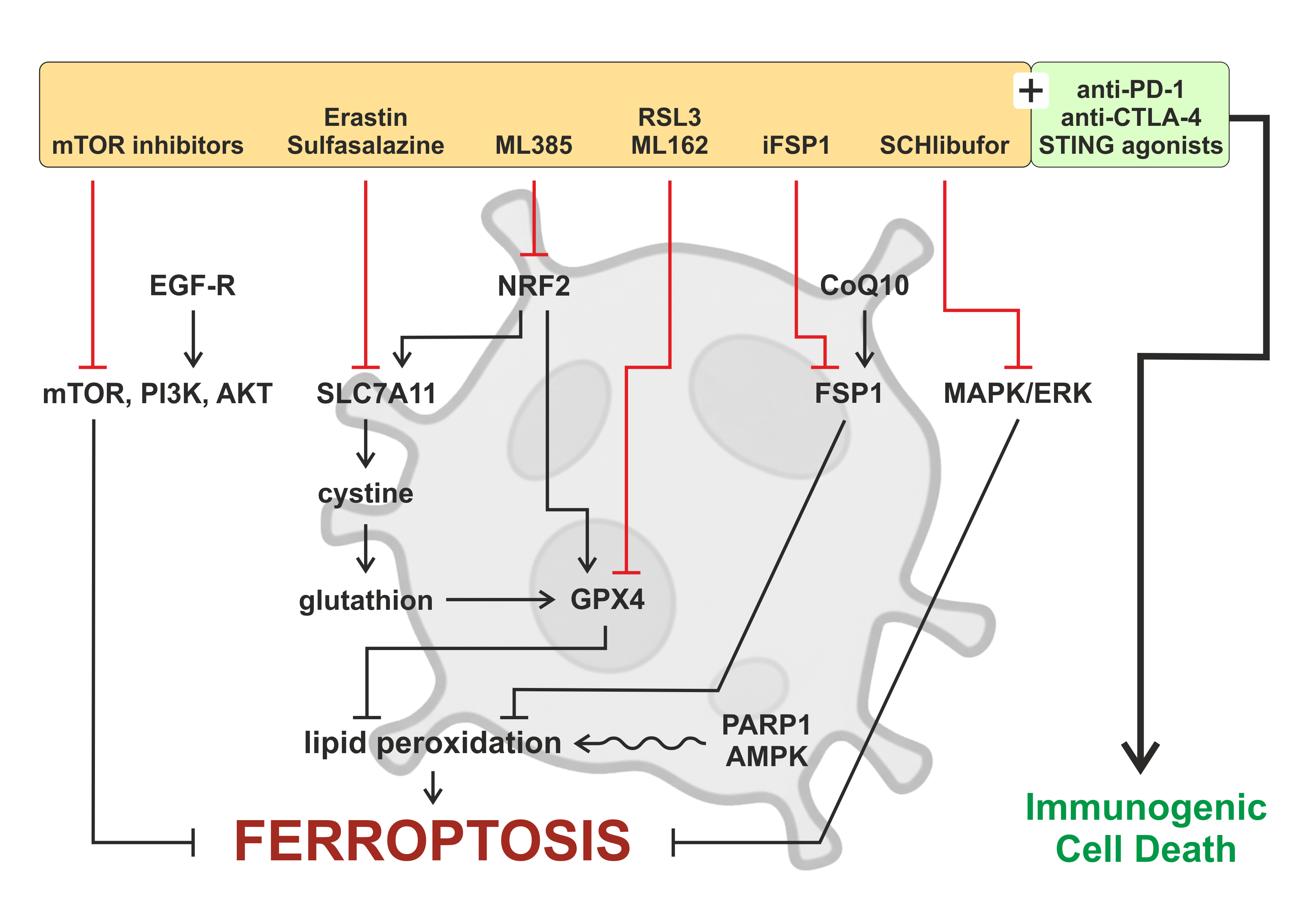

Combining Notch pathway inhibition with ferroptosis induction offers a promising synthetic-lethal therapeutic strategy. Notch signaling supports the maintenance of cancer stem-cell populations, and its blockade can sensitize tumor cells to ferroptotic death. In NSCLC, Notch3 knockdown increases ROS levels, enhances lipid peroxidation, and reduces GPX4 and PRDX6 expression, collectively driving ferroptotic cell death. Conversely, overexpression of the Notch3 intracellular domain protects cells from erastin-induced ferroptosis and provides ferroptosis resistance (49). Similarly, disruption of the Jag1/Notch1/3 axis in hepatic stellate cells decreased GPX4 levels and promoted ferroptosis (50). These findings support the therapeutic potential of co-targeting Notch signaling and ferroptosis regulators to eliminate tumor cells. While preclinical evidence is compelling, clinical validation is required to determine the safety and efficacy of these synthetic-lethal strategies (91-93). PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling, which can be activated downstream of EGFR, promotes lipid biosynthesis and supports cell survival. Consequently, inhibition of this pathway increases cellular vulnerability to ferroptotic stress. Synthetic-lethality strategies target these resistance nodes. GPX4 inhibitors (such as RSL3 or ML162) block detoxification of lipid peroxides, whereas system Xc⁻ inhibitors (such as Erastin or Sulfasalazine) deplete cystine and GSH. Modulators of MAPK/ERK, AMPK, and PARP1 signaling can further influence ferroptotic sensitivity by altering lipid metabolism and stress-response pathways. Combination therapies, particularly ferroptosis inducers paired with immune checkpoint blockade (anti-PD-1 or anti-CTLA-4) or with STING agonists, enhance tumor immunogenicity and can overcome resistance to monotherapies in preclinical models (77,78). These integrated therapeutic designs highlight opportunities to exploit ferroptosis vulnerabilities across diverse tumor subtypes.

Despite these combination strategies, tumor cells frequently resist ferroptosis through multiple pathways. SLC7A11-mediated cystine uptake supports glutathione synthesis, which detoxifies lipid peroxides via GPX4. NRF2 activation upregulates antioxidant genes, including SLC7A11; ML385 inhibition sensitizes cells to ferroptosis. Parallel resistance mechanisms include the FSP1-CoQ10 pathway, which provides GSH-independent suppression of lipid peroxidation, and the GCH1-BH4 axis, which stabilizes phospholipid membranes and protects against oxidative damage. Figure 3 illustrates the molecular mechanisms by which cancer cells evade ferroptosis and highlights synthetic lethality strategies designed to restore ferroptotic sensitivity.

Figure 3. Drug resistance and synthetic lethality to overcome ferroptosis resistance. Schematic illustration depicting the multifaceted roles of autophagy in shaping the tumor microenvironment (TME) and antitumor immunity. Autophagy within tumor cells, immune cells, and stromal components regulates metabolic adaptation, antigen processing and presentation, cytokine secretion, and stress responses under conditions such as hypoxia and nutrient deprivation. These autophagy-dependent processes influence the functional states of key TME constituents, including tumor-associated macrophages, dendritic cells, cancer-associated fibroblasts, natural killer cells, and cytotoxic T lymphocytes, thereby modulating immune activation or immune evasion. In parallel, autophagy can promote immunogenic cell death, enhancing tumor antigen release and immune recognition, while excessive or dysregulated autophagy may facilitate therapy resistance and immune suppression. Collectively, the figure highlights autophagy as a context-dependent regulator that integrates metabolic and immune signals to remodel the TME and dynamically affect therapeutic responses.

6.4. Therapeutic considerations

Favorable therapeutic windows for ferroptosis-based interventions arise in tumors that naturally accumulate high levels of polyunsaturated phospholipids (PUFA‑PLs), exhibit elevated ROS, or display increased iron influx, particularly when these features coincide with weakened antioxidant defenses. Such conditions create an intrinsic vulnerability to lipid peroxidation and ferroptotic stress. These windows tend to be particularly pronounced in tumor types such as TNBC, KRAS-mutant pancreatic cancer, GBM, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), and Notch3-driven NSCLC, all of which exhibit metabolic or redox profiles that increase ferroptosis susceptibility.

Toxicity remains a significant concern when manipulating ferroptosis or blocking Notch signaling for therapeutic purposes. Uncontrolled ferroptosis can injure organs that are particularly sensitive to oxidative stress, including the kidney, liver, and heart. Notch inhibition presents its own challenges: because the pathway helps maintain epithelial integrity, patients may experience gastrointestinal side effects, vascular complications, or changes in goblet cell populations. Adding ferroptosis inducers to immune-based treatments introduces an additional layer of risk, as heightened immune activation and elevated reactive oxygen species may drive responses beyond a tolerable range. To address these issues, researchers are investigating approaches such as nanoparticle-guided delivery for better tumor targeting, treatment schedules that limit continuous exposure, and biomarker-driven selection of patients who are more likely to tolerate and benefit from these interventions.

Nanoparticle-based delivery systems are being developed to enhance ferroptosis induction specifically within tumors while minimizing systemic toxicity. For example, PD-1 membrane-coated polymeric nanoparticles encapsulating the ferroptosis inducer RSL3 have been shown to promote lipid peroxidation-mediated tumor cell death and simultaneously activate antitumor immunity in breast cancer models (94). Similarly, nanocarrier formulations such as liposomes, metal-organic frameworks, and polymeric micelles improve the pharmacokinetic stability and tumor-specific accumulation of ferroptosis inducers, enhancing therapeutic efficacy while reducing off-target effects (95).

Recently, CRISPR-based functional genomic screens have been used to identify regulators of ferroptosis sensitivity. Large-scale activation screens revealed that SWI/SNF chromatin-remodeling ATPases, including SMARCA2 and SMARCA4, act as key suppressors of ferroptosis, protecting tumor cells from lipid peroxidation-induced death (96). Targeting these ATPases or other chromatin-regulatory mechanisms may enhance ferroptosis induction and improve therapeutic responses. Moreover, CRISPR technology enables systematic mapping of ferroptosis gene networks, facilitating the rational design of drug combinations that exploit ferroptosis-Notch vulnerabilities.

Finally, integrative multi-omics analyses encompassing genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics are increasingly used to classify patients based on ferroptosis-related gene signatures (e.g., ACSL4, FSP1, NFE2L2) (97). Machine learning algorithms trained on these datasets can predict ferroptosis sensitivity and inform therapeutic strategies (98). By combining genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic data, researchers can identify ferroptosis-associated signatures across cancer cohorts, enabling patient stratification and the development of personalized therapies targeting ferroptosis and related pathways (99,100).

Discussion

Future research should define the precise cellular and molecular contexts regulating ferroptosis. Targeting NRF2 or downstream antioxidant pathways may increase tumor susceptibility to ferroptosis-inducing therapies. Next-generation preclinical platforms, including patient-derived organoids (PDOs) and organoid xenografts (PDOXs), will be essential for assessing ferroptosis within physiologically relevant tumor microenvironments (110). In parallel, single-cell RNA sequencing and spatial transcriptomics can uncover heterogeneity in ferroptosis sensitivity and distinct metabolic and redox states across tumors (111). Integrating CRISPR-based screens, multi-omics analyses, and AI-driven modeling may establish robust frameworks for predicting ferroptosis responsiveness and informing personalized therapeutic strategies. Collectively, these efforts aim to translate ferroptosis and Notch pathway modulation into clinically viable approaches that advance precision oncology.

Despite growing interest in therapeutically modulating ferroptosis and Notch signaling, clinical translation remains challenging. A significant challenge is the context-dependent nature of Notch signaling. In some cancers, Notch acts as an oncogene, promoting proliferation and metastasis (101-103); in others, it functions as a tumor suppressor by promoting differentiation or restricting growth. This dual role depends on cancer type, cellular context, genetic background, and specific cell populations within a tumor. Consequently, while Notch inhibition is effective in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) driven by gain-of-function NOTCH1 mutations, the development of broad-spectrum Notch inhibitors is complicated (104).

Tumor heterogeneity also generates a complex landscape of ferroptosis sensitivity. For example, hyperactivation of NRF2 in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and lung adenocarcinoma enhances antioxidant defenses, including GPX4 and SLC7A11, reducing susceptibility to ferroptosis inducers (105). Adaptive resistance mechanisms further challenge both ferroptosis and Notch-targeted therapies. Prolonged induction of ferroptosis can upregulate FSP1, thereby bypassing GPX4 dependence, whereas resistance to γ-secretase inhibitors (GSIs) may arise through alternative survival pathways, such as PI3K/AKT or Wnt signaling (106,107). Additionally, cancer stem cells (CSCs), often regulated by Notch, can adapt to ferroptotic stress, promoting recurrence and metastasis (108,109). Most current data are derived from in vitro studies, underscoring the need for additional in vivo validation, particularly in models that reflect TME dynamics and drug resistance.

Taken together, current evidence indicates that Notch signaling is an essential regulator of ferroptosis in both malignant and normal tissues, in part by shaping antioxidant capacity and iron handling. When this pathway remains active, cells are often better equipped to avoid ferroptotic death, a feature that can undermine the effectiveness of specific therapies. For this reason, several groups are now exploring whether blocking Notch while inducing ferroptosis might enhance therapeutic responses in tumors that are resistant to standard treatment. As more datasets integrate genomic, transcriptomic, and metabolic information, the molecular links between these pathways are becoming clearer, which may eventually guide the development of more selective therapeutic approaches. Although much remains to be determined, adjusting ferroptosis alongside Notch activity could alter how some cancers are managed and may expand treatment options for patients with difficult-to-treat disease.

References

1. Dixon SJ, Lemberg KM, Lamprecht MR, Skouta R, Zaitsev EM, Gleason CE, et al. Ferroptosis: an iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell. 2012;149(5):1060–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.042

2. Seiler A, Schneider M, Förster H, Roth S, Wirth EK, Culmsee C, et al. Glutathione peroxidase 4 senses and translates oxidative stress into 12/15-lipoxygenase dependent and AIF-mediated cell death. Cell Metab. 2008;8(3):237–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2008.07.005

3. Yant LJ, Ran Q, Rao L, Van Remmen H, Shibatani T, Belter JG, et al. The selenoprotein GPX4 is essential for mouse development and protects from radiation and oxidative damage insults. Free Radic Biol Med. 2003;34(4):496–502. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0891-5849(02)01360-6

4. Doll S, Proneth B, Tyurina YY, Panzilius E, Kobayashi S, Ingold I, et al. ACSL4 dictates ferroptosis sensitivity by shaping cellular lipid composition. Nat Chem Biol. 2017;13(1):91–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/nchembio.2239

5. Yuan H, Li X, Zhang X, Kang R, Tang D. Identification of ACSL4 as a biomarker and contributor of ferroptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2016;478(3):1338–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.08.124

6. Friedmann Angeli JP, Schneider M, Proneth B, Tyurina YY, Tyurin VA, Hammond VJ, et al. Inactivation of the ferroptosis regulator Gpx4 triggers acute renal failure in mice. Nat Cell Biol. 2014;16(12):1180–91. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncb3064

7. Metz CW, Bridges CB. Incompatibility of mutant races in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1917;3(12):673–8. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.3.12.673

8. Mohr OL. Character changes caused by mutation of an entire region of a chromosome in Drosophila. Genetics. 1919;4(3):275–82. https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/4.3.275

9. Bridges CB. Non-disjunction as proof of the chromosome theory of heredity (concluded). Genetics. 1916;1(2):107–63. https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/1.2.107

10. Wharton KA, Johansen KM, Xu T, Artavanis-Tsakonas S. Nucleotide sequence from the neurogenic locus notch implies a gene product that shares homology with proteins containing EGF-like repeats. Cell. 1985;43(3 Pt 2):567–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/0092-8674(85)90229-6

11. Kidd S, Kelley MR, Young MW. Sequence of the notch locus of Drosophila melanogaster: relationship of the encoded protein to mammalian clotting and growth factors. Mol Cell Biol. 1986;6(9):3094–3108. https://doi.org/10.1128/mcb.6.9.3094-3108.1986

12. Vässin H, Campos-Ortega JA. Genetic analysis of Delta, a neurogenic gene of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1987;116(3):433–445. https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/116.3.433

13. Gordon WR, Vardar-Ulu D, Histen G, Sanchez-Irizarry C, Aster JC, Blacklow SC. Structural basis for autoinhibition of Notch. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14(4):295–300. https://doi.org/10.1038/nsmb1227

14. Kopan R, Ilagan MX. The canonical Notch signaling pathway: unfolding the activation mechanism. Cell. 2009;137(2):216–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.045

15. Wang H, Zou J, Zhao B, Johannsen E, Ashworth T, Wong H, et al. Genome-wide analysis reveals conserved and divergent features of Notch1/RBPJ binding in human and murine T-lymphoblastic leukemia cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(36):14908–13. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1109023108

16. Takebe N, Nguyen D, Yang SX. Targeting Notch signaling pathway in cancer: clinical development advances and challenges. Pharmacol Ther. 2014;141(2):140–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharmthera.2013.09.005

17. Borggrefe T, Oswald F. The Notch signaling pathway: transcriptional regulation at Notch target genes. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66(10):1631–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-009-8668-7

18. Palmer WH, Deng WM. Ligand-Independent Mechanisms of Notch Activity. Trends Cell Biol. 2015;25(11):697–707. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tcb.2015.07.010

19. Zhao J, Ma W, Wang S, Zhang K, Xiong Q, Li Y, et al. Differentiation of intestinal stem cells toward goblet cells under systemic iron overload stress are associated with inhibition of Notch signaling pathway and ferroptosis. Redox Biol. 2024;72:103160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2024.103160

20. Ning J, Qiao L. Ferroptosis: molecular mechanisms, pathophysiology, and role in pediatric pulmonary diseases. Cell Biol Toxicol. 2025;41(1):144. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10565-025-10100-z

21. Chang C, Wang M, Li J, Qi S, Yu X, Xu J, et al. Targeting NOTCH1-KEAP1 axis retards chronic liver injury and liver cancer progression via regulating stabilization of NRF2. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2025;44(1):232. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13046-025-03488-3

22. Liu X, Chen C, Han D, Zhou W, Cui Y, Tang X, et al. SLC7A11/GPX4 inactivation-mediated ferroptosis contributes to the pathogenesis of triptolide-induced cardiotoxicity. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2022;2022:3192607. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/3192607

23. Wei J, Zhu L. The role of glutathione peroxidase 4 in the progression, drug resistance, and targeted therapy of non-small cell lung cancer. Oncol Res. 2025;33(4):863–872. https://doi.org/10.32604/or.2024.054201

24. Doll S, Conrad M. Iron and ferroptosis: A still ill-defined liaison. IUBMB Life. 2017;69(6):423–434. https://doi.org/10.1002/iub.1616

25. Wang Z, Shen N, Wang Z, Yu L, Yang S, Wang Y, et al. TRIM3 facilitates ferroptosis in non-small cell lung cancer through promoting SLC7A11/xCT K11-linked ubiquitination and degradation. Cell Death Differ. 2024;31(1):53–64. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41418-023-01239-5

26. Pontel LB, Bueno-Costa A, Morellato AE, Carvalho Santos J, Roué G, Esteller M. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia necessitates GSH-dependent ferroptosis defenses to overcome FSP1-epigenetic silencing. Redox Biol. 2022;55:102408. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2022.102408

27. Shen N, Li M, Fang B, Li X, Jiang F, Zhu T, et al. ALOX15-driven ferroptosis: the key target in dihydrotanshinone I's epigenetic battle in hepatic stellate cells against liver fibrosis. Int Immunopharmacol. 2025;146:113827. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intimp.2024.113827

28. Ye H, Wu L, Liu YM, Zhang JX, Hu HT, Dong ML, et al. Wogonin attenuates septic cardiomyopathy by suppressing ALOX15-mediated ferroptosis. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2025;46(9):2407-2422. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41401-025-01547-1

29. Xie LH, Fefelova N, Pamarthi SH, Gwathmey JK. Molecular mechanisms of ferroptosis and relevance to cardiovascular disease. Cells. 2022;11(17):2726. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11172726

30. Bersuker K, Hendricks JM, Li Z, Magtanong L, Ford B, Tang PH, et al. The CoQ oxidoreductase FSP1 acts parallel to GPX4 to inhibit ferroptosis. Nature. 2019;575(7784):688–692. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1705-2

31. Mishima E, Nakamura T, Zheng J, Zhang W, Mourão ASD, Sennhenn P, et al. DHODH inhibitors sensitize to ferroptosis by FSP1 inhibition. Nature. 2023;619(7968):E9–E18. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06269-0

32. Kang R, Kroemer G, Tang D. The tumor suppressor protein p53 and the ferroptosis network. Free Radic Biol Med. 2019;133:162–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2018.05.074

33. Jiang L, Kon N, Li T, Wang SJ, Su T, Hibshoosh H, et al. Ferroptosis as a p53-mediated activity during tumour suppression. Nature. 2015;520(7545):57–62. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14344

34. Tarangelo A, Magtanong L, Bieging-Rolett KT, Li Y, Ye J, Attardi LD, et al. p53 suppresses metabolic stress-induced ferroptosis in cancer cells. Cell Rep. 2018;22(3):569–575. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2017.12.077

35. Pei Y, Qian Y, Wang H, Tan L. Epigenetic regulation of ferroptosis-associated genes and its implication in cancer therapy. Front Oncol. 2022;12:771870. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2022.771870

36. Zhang L, Chen F, Dong J, Wang R, Bi G, Xu D, et al. HDAC3 aberration-incurred GPX4 suppression drives renal ferroptosis and AKI-CKD progression. Redox Biol. 2023;68:102939. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2023.102939

37. Wu J, Zhu S, Wang P, Wang J, Huang J, Wang T, et al. Regulators of epigenetic change in ferroptosis‑associated cancer (Review). Oncol Rep. 2022;48(6):215. https://doi.org/10.3892/or.2022.8430

38. Zhang X, Zhang Y, Wei J, Li X, Jiang A, Shen Y, et al. The Role of SLC7A11 in Tumor Progression and the Regulation Mechanisms Involved in Ferroptosis. Cancer Manag Res. 2025;17:2393–2401. https://doi.org/10.2147/CMAR.S551549

39. Wang M, Mao C, Ouyang L, Liu Y, Lai W, Liu N, et al. Long noncoding RNA LINC00336 inhibits ferroptosis in lung cancer by functioning as a competing endogenous RNA. Cell Death Differ. 2019;26(11):2329–2343. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41418-019-0304-y

40. Yang J, Cao XH, Luan KF, Huang YD. Circular RNA FNDC3B protects oral squamous cell carcinoma cells from ferroptosis and contributes to the malignant progression by regulating miR-520d-5p/SLC7A11 axis. Front Oncol. 2021;11:672724. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2021.672724

41. Lei G, Zhuang L, Gan B. Targeting ferroptosis as a vulnerability in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2022;22(7):381–396. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41568-022-00459-0

42. Schnute B, Shimizu H, Lyga M, Baron M, Klein T. Ubiquitylation is required for the incorporation of the Notch receptor into intraluminal vesicles to prevent prolonged and ligand-independent activation of the pathway. BMC Biol. 2022;20(1):65. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12915-022-01245-y

43. Miao X, Yue W, Wang J, Chen J, Qiu L, Paerhati H, et al. Unraveling the role of perivascular macrophages in Alzheimer's disease: insights from the crosstalk between immunometabolism and ferroptosis. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2025. Epub ahead of print. https://doi.org/10.2174/011570159X417328250908080404

44. Wang SS, Lv HL, Nie RZ, Liu YP, Hou YJ, Chen C, et al. Notch signaling in cancer: metabolic reprogramming and therapeutic implications. Front Immunol. 2025;16:1656370. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2025.1656370

45. Gan B. ACSL4, PUFA, and ferroptosis: new arsenal in anti-tumor immunity. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022;7(1):128. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-022-01004-z

46. Fan H, Paiboonrungruan C, Zhang X, Prigge JR, Schmidt EE, Sun Z, et al. Nrf2 regulates cellular behaviors and Notch signaling in oral squamous cell carcinoma cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017;493(1):833–839. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.08.049

47. Liu S, Liu J, Wang Y, Deng F, Deng Z. Oxidative stress: signaling pathways, biological functions, and disease. MedComm. 2025;6(7):e70268. https://doi.org/10.1002/mco2.70268

48. Liu S, Wu H, Zhang P, Zhou H, Wu D, Jin Y, et al. NELL2 suppresses epithelial-mesenchymal transition and induces ferroptosis via notch signaling pathway in HCC. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):10193. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94669-9

49. Li Z, Xiao J, Liu M, Cui J, Lian B, Sun Y, et al. Notch3 regulates ferroptosis via ROS-induced lipid peroxidation in NSCLC cells. FEBS Open Bio. 2022;12(6):1197–1205. https://doi.org/10.1002/2211-5463.13393

50. Li X, Li Y, Zhang W, Jiang F, Lin L, Wang Y, et al. The IGF2BP3/Notch/Jag1 pathway: A key regulator of hepatic stellate cell ferroptosis in liver fibrosis. Clin Transl Med. 2024;14(8):e1793. https://doi.org/10.1002/ctm2.1793

51. Zhu WW, Liu Y, Yu Z, Wang HQ. SLC7A11-mediated cell death mechanism in cancer: a comparative study of disulfidptosis and ferroptosis. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2025;13:1559423. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2025.1559423

52. Auberger P, Favreau C, Savy C, Jacquel A, Robert G. Emerging role of glutathione peroxidase 4 in myeloid cell lineage development and acute myeloid leukemia. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 2024;29(1):98. https://doi.org/10.1186/s11658-024-00613-6

53. Mathew M, Sivaprakasam S, Dharmalingam-Nandagopal G, Sennoune SR, Nguyen NT, Jaramillo-Matinez V, et al. Induction of oxidative stress and ferroptosis in triple-negative breast cancer cells by niclosamide via blockade of the function and expression of SLC38A5 and SLC7A11. Antioxidants (Basel). 2024;13(3):291. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox13030291

54. Xu J, Bai X, Dong K, Du Q, Ma P, Zhang Z, et al. GluOC induced SLC7A11 and SLC38A1 to activate redox processes and resist ferroptosis in TNBC. Cancers (Basel). 2025;17(5):739. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17050739

55. Koppula P, Zhuang L, Gan B. Cystine transporter SLC7A11/xCT in cancer: ferroptosis, nutrient dependency, and cancer therapy. Protein Cell. 2021;12(8):599–620. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13238-020-00789-5

56. Banu MA, Dovas A, Argenziano MG, Zhao W, Sperring CP, Cuervo Grajal H, et al. A cell state-specific metabolic vulnerability to GPX4-dependent ferroptosis in glioblastoma. EMBO J. 2024;43(20):4492–4521. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44318-024-00176-4

57. Yang Z, Zhang T, Zhu X, Zhang X. Ferroptosis-related transcriptional level changes and the role of CIRBP in glioblastoma cells ferroptosis. Biomedicines. 2024;13(1):41. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13010041

58. Gersey Z, Osiason AD, Bloom L, Shah S, Thompson JW, Bregy A, et al. Therapeutic Targeting of the Notch Pathway in Glioblastoma Multiforme. World Neurosurg. 2019;131:252–263.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2019.07.180

59. Zhang S, Li X, Li X, Zhang Z, Zhu K, Guo J. Development of a ferroptosis-related signature and identification of NOTCH2 as a novel prognostic biomarker in pancreatic cancer. Front Immunol. 2025;16:1659652. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2025.1659652

60. Qiao Y, Su M, Zhao H, Liu H, Wang C, Dai X, et al. Targeting FTO induces colorectal cancer ferroptotic cell death by decreasing SLC7A11/GPX4 expression. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2024;43(1):108. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13046-024-03032-9

61. Liu L, Qiu Y, Peng Z, Yu Z, Lu H, Xie R, et al. Genistein induces ferroptosis in colorectal cancer cells via FoxO3/SLC7A11/GPX4 signaling pathway. J Cancer. 2024;15(20):6741–6753. https://doi.org/10.7150/jca.95775

62. Sadagopan NS, Gomez M, Tripathi S, Billingham LK, DeLay SL, Cady MA, et al. NOTCH3 drives fatty acid oxidation and ferroptosis resistance in aggressive meningiomas. J Neurooncol. 2025;175(3):979–991. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-025-05208-0

63. Ma Y, Zhang X, Alsaidan OA, Yang X, Sulejmani E, Zha J, et al. Long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase 4-mediated fatty acid metabolism sustains androgen receptor pathway-independent prostate cancer. Mol Cancer Res. 2021;19(1):124–135. https://doi.org/10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-20-0379

64. Marignol L, Rivera-Figueroa K, Lynch T, Hollywood D. Hypoxia, notch signalling, and prostate cancer. Nat Rev Urol. 2013;10(7):405–413. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrurol.2013.110

65. Cui K, Wang K, Huang Z. Ferroptosis and the tumor microenvironment. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2024;43(1):315. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13046-024-03235-0

66. He H, Yu H, Zhou H, Cui G, Shao M. Natural compounds as modulators of ferroptosis: mechanistic insights and therapeutic prospects in breast cancer. Biomolecules. 2025;15(9):1308. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15091308

67. Garg AD, Romano E, Rufo N, Angostinis P. Immunogenic versus tolerogenic phagocytosis during anticancer therapy: mechanisms and clinical translation. Cell Death Differ. 2016;23(6):938–951. https://doi.org/10.1038/cdd.2016.5

68. Tang R, Xu J, Zhang B, Liu J, Liang C, Hua J, et al. Ferroptosis, necroptosis, and pyroptosis in anticancer immunity. J Hematol Oncol. 2020;13(1):110. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-020-00946-7

69. Wen Q, Liu J, Kang R, Zhou B, Tang D. The release and activity of HMGB1 in ferroptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2019;510(2):278–283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.01.090

70. Tang D, Kepp O, Kroemer G. Ferroptosis becomes immunogenic: implications for anticancer treatments. Oncoimmunology. 2020;10(1):1862949. https://doi.org/10.1080/2162402X.2020.1862949

71. Demuynck R, Efimova I, Naessens F, Krysko DV. Immunogenic ferroptosis and where to find it? J Immunother Cancer. 2021;9(12):e003430. https://doi.org/10.1136/jitc-2021-003430

72. Wang W, Green M, Choi JE, Gijón M, Kennedy PD, Johnson JK, et al. CD8+ T cells regulate tumour ferroptosis during cancer immunotherapy. Nature. 2019;569(7755):270–274. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1170-y

73. Woo SR, Fuertes MB, Corrales L, Spranger S, Furdyna MJ, Leung MY, et al. STING-dependent cytosolic DNA sensing mediates innate immune recognition of immunogenic tumors. Immunity. 2014;41(5):830–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2014.10.017

74. Ioannidis M, Tjepkema J, Uitbeijerse MRP, van den Bogaart G. Immunomodulatory effects of 4-hydroxynonenal. Redox Biol. 2025;85:103719. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2025.103719

75. Li JY, Yao YM, Tian YP. Ferroptosis: a trigger of proinflammatory state progression to immunogenicity in necroinflammatory disease. Front Immunol. 2021;12:701163. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2021.701163

76. Meng Y, Zhou Q, Dian Y, Zeng F, Deng G, Chen X. Ferroptosis: a targetable vulnerability for melanoma treatment. J Invest Dermatol. 2025;145(6):1323–1344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jid.2024.11.007

77. Deng J, Zhou M, Liao T, Kuang W, Xia H, Yin Z, et al. Targeting cancer cell ferroptosis to reverse immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy resistance. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2022;10:818453. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2022.818453

78. Wang X, He J, Ding G, Tang Y, Wang Q. Overcoming resistance to PD-1 and CTLA-4 blockade mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. Front Immunol. 2025;3(16):1688699. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2025.1688699

79. Yang WS, SriRamaratnam R, Welsch ME, Shimada K, Skouta R, Viswanathan VS, et al. Regulation of ferroptotic cancer cell death by GPX4. Cell. 2014;156(1-2):317–331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.010

80. Wu C, Zhao Y, Wang J, Ma L. Unraveling the dual nature of GPx4: From ferroptosis regulation to therapeutic innovation in human pathologies. Med Res Arch. 2025;13(8). https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i8.6801

81. Sleire L, Skeie BS, Netland IA, Førde HE, Dodoo E, Selheim F, et al. Drug repurposing: sulfasalazine sensitizes gliomas to gamma knife radiosurgery by blocking cystine uptake through system Xc-, leading to glutathione depletion. Oncogene. 2015;34(49):5951–5959. https://doi.org/10.1038/onc.2015.60

82. Sato M, Kusumi R, Hamashima S, Kobayashi S, Sasaki S, Komiyama Y, et al. The ferroptosis inducer erastin irreversibly inhibits system xc- and synergizes with cisplatin to increase cisplatin's cytotoxicity in cancer cells. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):968. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-19213-4

83. Yu L, Huang K, Liao Y, Wang L, Sethi G, Ma Z. Targeting novel regulated cell death: ferroptosis, pyroptosis and necroptosis in anti-PD-1/PD-L1 cancer immunotherapy. Cell Prolif. 2024;57(8):e13644. https://doi.org/10.1111/cpr.13644

84. Mokhtarpour K, Razi S, Rezaei N. Ferroptosis as a promising targeted therapy for triple negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2024;207(3):497–513. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-024-07387-7

85. Gudsoorkar P, Wanchoo R, Jhaveri KD. Nirogacestat and hypophosphatemia. Kidney Int Rep. 2023;8(7):1478. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ekir.2023.04.023

86. Pietanza MC, Spira AI, Jotte RM, Gadgeel SM, Mita AC, Hart LL, et al. Final results of phase Ib of tarextumab (TRXT, OMP-59R5, anti-Notch2/3) in combination with etoposide and platinum (EP) in patients (pts) with untreated extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer (ED-SCLC). J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(15_suppl):7508. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2015.33.15_suppl.7508

87. Casulo C, Ruan J, Dang NH, Gore L, Diefenbach C, Beaven AW, et al. Safety and preliminary efficacy results of a phase I first-in-human study of the novel Notch-1 targeting antibody brontictuzumab (OMP-52M51) administered intravenously to patients with hematologic malignancies. Blood. 2016;128(22):5108. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.V128.22.5108.5108

88. Smith DC, Eisenberg PD, Manikhas G, Chugh R, Gubens MA, Stagg RJ, et al. A phase I dose escalation and expansion study of the anticancer stem cell agent demcizumab (anti-DLL4) in patients with previously treated solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20(24):6295–6303. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1373

89. Cao J, Chen X, Chen L, Lu Y, Wu Y, Deng A, et al. DHODH-mediated mitochondrial redox homeostasis: a novel ferroptosis regulator and promising therapeutic target. Redox Biol. 2025;85:103788. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2025.103788

90. Mao C, Liu X, Zhang Y, Lei G, Yan Y, Lee H, et al. DHODH-mediated ferroptosis defence is a targetable vulnerability in cancer. Nature. 2021;593(7860):586–590. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03539-7

91. Ni Y, Liu L, Jiang F, Wu M, Qin Y. JAG1/Notch pathway inhibition induces ferroptosis and promotes cataractogenesis. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26(1):307. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms26010307

92. Wang L, Zhu Y, Huang C, Pan Q, Wang J, Li H, et al. Targeting ferroptosis in cancer stem cells: a novel strategy to improve cancer treatment. Genes Dis. 2025;12(6):101678. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gendis.2025.101678

93. Kinowaki Y, Taguchi T, Onishi I, Kirimura S, Kitagawa M, Yamamoto K. Overview of ferroptosis and synthetic lethality strategies. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(17):9271. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22179271

94. Mu Y, Fan Y, He L, Hu N, Xue H, Guan X, et al. Enhanced cancer immunotherapy through synergistic ferroptosis and immune checkpoint blockade using cell membrane-coated nanoparticles. Cancer Nano. 2023;14:83. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12645-023-00234-2

95. Dhas N, Kudarha R, Tiwari R, Tiwari G, Garg N, Kumar P, et al. Recent advancements in nanomaterial-mediated ferroptosis-induced cancer therapy: Importance of molecular dynamics and novel strategies. Life Sci. 2024;346:122629. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2024.122629

96. Bhat KP, Vijay J, Vilas CK, Asundi J, Zou J, Lau T, et al. CRISPR activation screens identify the SWI/SNF ATPases as suppressors of ferroptosis. Cell Rep. 2024;43(6):114345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2024.114345

97. Guo Q, Xie M, Wang X, Han C, Gao G, Wang QN, et al. Multi-omic serum analysis reveals ferroptosis pathways and diagnostic molecular signatures associated with Moyamoya diseases. J Neuroinflammation. 2025;22(1):123. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12974-025-03446-y

98. Li Z, Chen Y, Hou B, Mi Y, Fu C, Han Z, et al. Machine learning constructs a ferroptosis related signature for predicting prognosis and drug sensitivity in lung cancer. Cell Oncol (Dordr). 2025;48(6):1971-1986. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13402-025-01121-1

99. Luo Y, Tang L, Zeng Z, Trang D, Mo D, Yang Y. Ferroptosis and cellular senescence-related genes in cervical cancer: mechanistic insights from multi-omics and clinical sample analysis. Transl Oncol. 2025;60:102487. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranon.2025.102487

100. Hu J, Song F, Kang W, Xia F, Song Z, Wang Y, et al. Integrative analysis of multi-omics data for discovery of ferroptosis-related gene signature predicting immune activity in neuroblastoma. Front Pharmacol. 2023;14:1162563. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2023.1162563

101. Lobry C, Oh P, Mansour MR, Look AT, Aifantis I. Notch signaling: switching an oncogene to a tumor suppressor. Blood. 2014;123(16):2451–2459. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2013-08-355818

102. Bray SJ. Notch signalling: a simple pathway becomes complex. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7(9):678–689. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrm2009

103. Guo M, Niu Y, Xie M, Liu X, Li X. Notch signaling, hypoxia, and cancer. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1078768. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2023.1078768

104. Sarmento LM, Barata JT. Therapeutic potential of Notch inhibition in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia: rationale, caveats and promises. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2011;11(9):1403–1415. https://doi.org/10.1586/era.11.73

105. Sun X, Ou Z, Chen R, Niu X, Chen D, Kang R, et al. Activation of the p62-Keap1-NRF2 pathway protects against ferroptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Hepatology. 2016;63(1):173–184. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.28251

106. Nakamura T, Hipp C, Santos Dias Mourão A, Borggräfe J, Aldrovandi M, Henkelmann B, et al. Phase separation of FSP1 promotes ferroptosis. Nature. 2023;619(7969):371–377. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06255-6

107. Liu R, Chen Y, Liu G, Li C, Song Y, Cao Z, et al. PI3K/AKT pathway as a key link modulates the multidrug resistance of cancers. Cell Death Dis. 2020;11(9):797. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-020-02998-6

108. Pannuti A, Foreman K, Rizzo P, Osipo C, Golde T, Osborne B, et al. Targeting Notch to target cancer stem cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16(12):3141–52. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2823

109. Wang H, Zhang Z, Ruan S, Yan Q, Chen Y, Cui J, et al. Regulation of iron metabolism and ferroptosis in cancer stem cells. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1251561. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2023.1251561

110. Lu D, Xia B, Feng T, Qi G, Ma Z. The role of cancer organoids in ferroptosis, pyroptosis, and necroptosis: functions and clinical implications. Biomolecules. 2025;15(5):659. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15050659

111. He Z, Liu Z, Wang Q, Sima X, Zhao W, He C, et al. Single-cell and spatial transcriptome assays reveal heterogeneity in gliomas through stress responses and pathway alterations. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1452172. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2024.1452172

Declarations

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the Medical University of Bialystok (grant B.SUB.24.405)

Declaration of Competing Interest: The authors declare no financial or personal relationships with other individuals or organizations that could inappropriately influence or bias the content of this work. All authors have read the final version of the manuscript and confirm that there are no competing interests.

Consent for publication: All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript.

Use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) Disclosure: This article was written by human contributors. Artificial intelligence-based tools were used to improve grammar, language, and readability without affecting the article's scientific content, data interpretation, or conclusions. The authors reviewed and verified all content to ensure its accuracy and integrity.

Dual Use Research of Concern (DURC): “The authors confirm that this research does not constitute DURC as defined by the U.S. Government Policy for Oversight of Life Sciences DURC.”

Data Availability Statements (DAS): “No datasets were generated or analyzed in the current study.”

Ethics approval and consent to participate: Not applicable, as this study did not involve the conduct of research.

Authors’ affiliations

1 Department of Histology and Embryology, Medical University of Bialystok, Bialystok, Poland.

2 Centre for Medical Simulation, Medical University of Bialystok, Bialystok, Poland.

# Correspondence: Joanna Pancewicz: E-mail address: Joanna.Pancewicz@umb.edu.pl

CRediT authorship contribution statement: JP: original draft writing, final manuscript review/editing. WN: final manuscript review/editing. PMC: final manuscript review/editing. All authors contributed to the work and approved the final version of the manuscript.

ORCID ID

Joanna Pancewicz: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3194-9107

Wieslawa Niklinska: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4587-1323

Piotr M. Chodorowski: https://orcid.org/0009-0008-1548-1093

How to cite

Pancewicz J, Niklinska W, Chodorowski PM. Ferroptosis and Notch Signaling Drive Tumor Progression and Therapeutic Vulnerability. Cancer Biome and Targeted Therapy. Published online 2025 Dec.