REVIEW ARTICLE OPEN ACCESS

The Cancer Microbiome: Mechanistic and Translational Insights into Oncogenesis and Therapy

Yangyun Wang1*, Youyang Shi2*, Jingjing Duan3*, Haijia Tang2, Lei Chen3#, Sheng Liu2#, Jianfeng Yang3#

Received 2025 Oct 2

Accepted 2025 Nov 3

Epub ahead of print: December 2025

Published in issue 2026 Feb 15

Correspondence: Jianfeng Yang - Email: 0156333@163.com

Sheng Liu - Email: lslhtcm@163.com

Chen Lei - Email: joe8989@163.com

The author’s information is available at the end of the article.

© 2026 The Author(s). Published by GCINC Press. Open Access licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. To view a copy: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Abstract

The human microbiome, including bacteria, fungi, and viruses, is increasingly recognized as a key player in cancer development and progression. Established oncogenic microorganisms such as Helicobacter pylori, human papillomavirus, and hepatitis viruses account for nearly 15% of cancers worldwide. Recent sequencing studies have further revealed the presence of diverse microbial communities in organs previously thought to be sterile. Microbial dysbiosis can promote carcinogenesis through multiple mechanisms, including DNA damage and genomic instability, chronic inflammation, immune suppression, and metabolic reprogramming. Distinct microbial signatures have been identified across various central malignancies, including lung, oral, gastric, pancreatic, colorectal, hepatocellular, breast, prostate, and gynecological cancers, highlighting their potential for both diagnostic and prognostic applications. Moreover, modulation of the microbiome is emerging as a promising therapeutic strategy, with applications ranging from probiotics and prebiotics to enhancing responses to immunotherapy, chemotherapy, and fecal microbiota transplantation. This review synthesizes current knowledge of microbiome-cancer interactions, emphasizes their translational implications, and outlines future directions for leveraging the microbiome in precision oncology.

Keywords: Cancer microbiome, Tumor microenvironment, Microbial dysbiosis, Drug resistance, Microbiota, Biofilms, Host-microbe interactions.

1. Introduction

Cancer remains the second leading cause of mortality worldwide. While conventional paradigms have long attributed carcinogenesis primarily to genetic predisposition and environmental exposures, mounting evidence now illuminates a pivotal role for the microbiome in tumor initiation and progression.

Table 1: Cancer types and key microbial associations.

| Cancer Type | Associated Microbes | Mechanisms | Clinical Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lung | Veillonella (3-5), Fusobacterium (6), Akkermansia (7, 8) | Inflammation, immune modulation | Potential biomarker |

| Oral | Porphyromonas gingivalis (9), Fusobacterium nucleatum (10) | EMT, immune suppression | Diagnostic saliva tests |

| Gastric | Helicobacter pylori (11, 12), Candida albicans (13), EBV (14) | DNA damage, chronic gastritis, PD-L1 upregulation | Target for eradication therapy |

| Pancreatic | Malassezia, P. (15) gingivalis (16), Fusobacterium (17) | Complement activation, immune suppression | Prognostic biomarkers |

| Colorectal |

Fusobacterium nucleatum (18), Bacteroides fragilis (19), pks+ E. coli (20) |

DNA alkylation, T cell inhibition | Stool-based screening |

| Hepatocellular Carcinoma | Dysbiotic gut flora (21) | Bile acid metabolism, gut–liver axis | Microbiome–liver cancer therapy |

| Breast | Lactobacillus (22) | Estrogen metabolism, immune dysfunction | Tumor microbiome studies |

In this context, specific microbial infections, including those caused by viruses, bacteria, and fungi, are increasingly recognized as significant risk factors for cancer development. Epidemiological data indicate that approximately 15% of cancers globally can be attributed to infection with carcinogenic microbes, with this burden disproportionately affecting low and middle-income countries (1). Moreover, co-infection with multiple microbial agents may synergistically amplify the likelihood of cancer development. Notable contributors to this global cancer burden include Helicobacter pylori, human papillomavirus (HPV), hepatitis B and C viruses (HBV and HCV), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and human herpesviruses (HHV), each contributing to varying extents. These infection-associated cancers underscore the oncogenic potential of specific microbes. Importantly, accumulating evidence suggests that cancer risk is not limited to direct infection alone. Advances in sequencing and microbial ecology have revealed that the broader commensal microbiome, encompassing both classical pathogens and other microbes, also influences the tumor microenvironment, modulates immune surveillance, and impacts cancer-related processes. This paradigm shift has thus expanded the focus from isolated infectious microbes to the complex microbial communities that coexist within the human host.

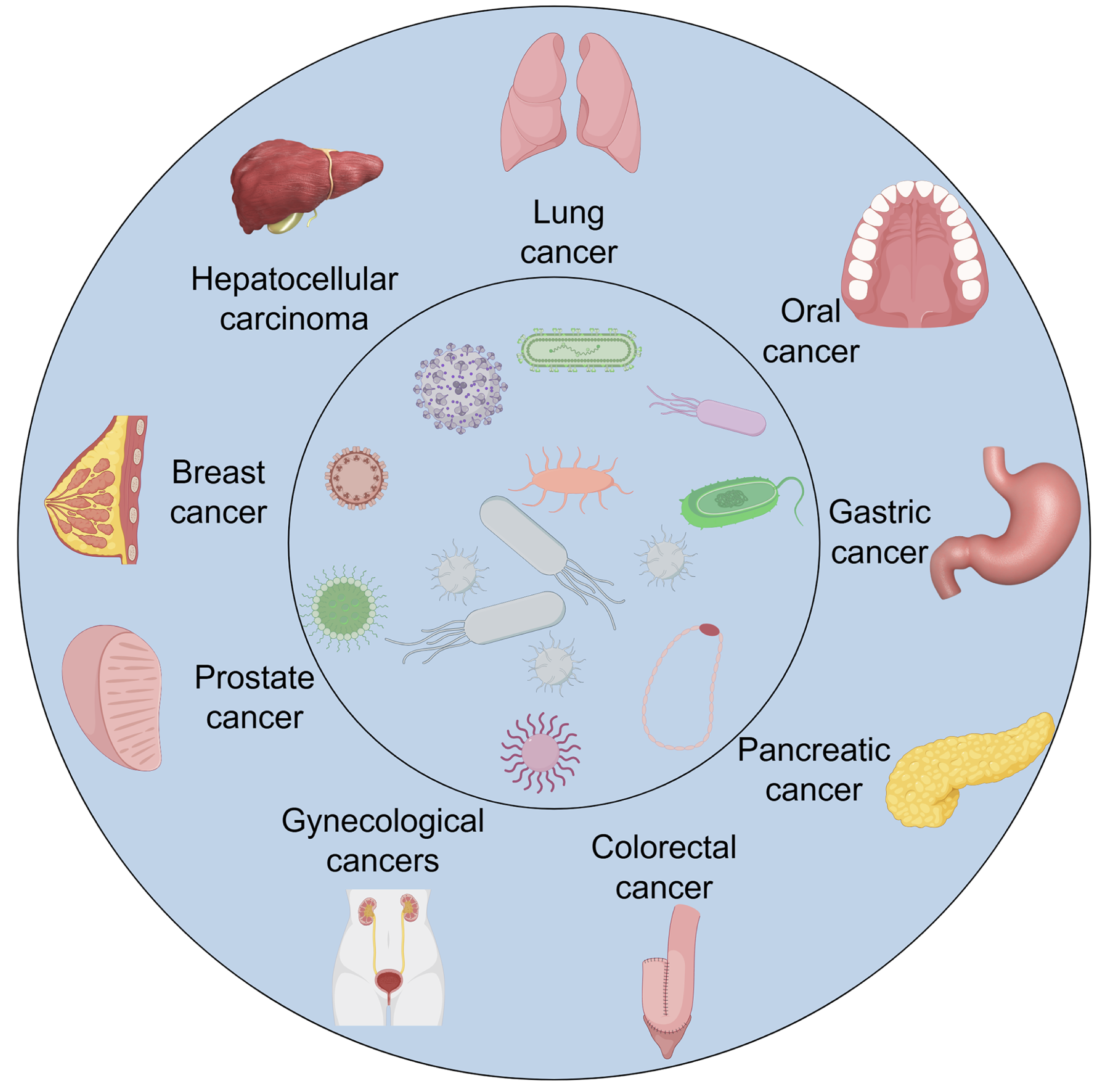

The human microbiome includes all microbial communities residing on and within the human body. It is intricately linked to multiple facets of host health and disease (2). Microbial ecosystems exist across virtually all examined human ecological niches. This includes the oral cavity, cutaneous surfaces, gastrointestinal tract, esophagus, lungs, and beyond (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Overview of the human microbiome and its interactions with the host. The figure provides a schematic overview of the human microbiome across major anatomical sites, including the gastrointestinal tract, oral cavity, respiratory system, urogenital tract, and skin. Each region harbors a distinct microbial community composed of bacteria, fungi, and viruses that work collectively to maintain host homeostasis. Microbiome–host interactions occur through immune signaling, metabolic crosstalk, and regulation of epithelial barrier integrity, supporting both local and systemic physiological balance. The diagram also highlights how disruptions in these interactions, referred to as dysbiosis, can lead to immune imbalance, chronic inflammation, and increased susceptibility to disease, including various cancers.

These complex microbiotas comprise diverse microorganisms, including bacteria, archaea, viruses, bacteriophages, and fungi. Together, they shape the ever-changing microbial environment of the human body. Disruptions in the gut microbial balance, often referred to as dysbiosis, are increasingly associated with tumor development. Gastric cancer is a clear example of the connection between microbial imbalance and host epithelial behavior. In addition to the well-known role of Helicobacter pylori, acid-tolerant bacteria, such as Lactobacillus, Veillonella, and Clostridium species, have been observed to increase in the stomach. This shift suggests their potential role in cancer development when the microbial balance is disrupted. In lung cancer, distinct microbial signatures associate with specific histological subtypes. Small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) is associated with increased prevalence of Kl, Acidovorax, Polaromonas, Rhodoferax, and Xylobacter. In contrast, non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients have elevated Ruminococcus spp., Akkermansia muciniphila, Eubacterium spp., and Alistipes spp. These differential patterns suggest that respiratory and gut microbiota may both contribute to lung cancer pathophysiology. This highlights the potential utility of the microbiome as a biomarker or therapeutic target in oncological management.

This review consolidates recent insights into the role of the microbiome in major cancer types, including lung, oral, pancreatic, gastric, colorectal, hepatocellular, breast, prostate, and gynecological cancers. The review connects the mechanistic bases discussed above with prospective clinical strategies. It also highlights future directions for translational research in this rapidly evolving field.

2. The link between microbiome and cancer development

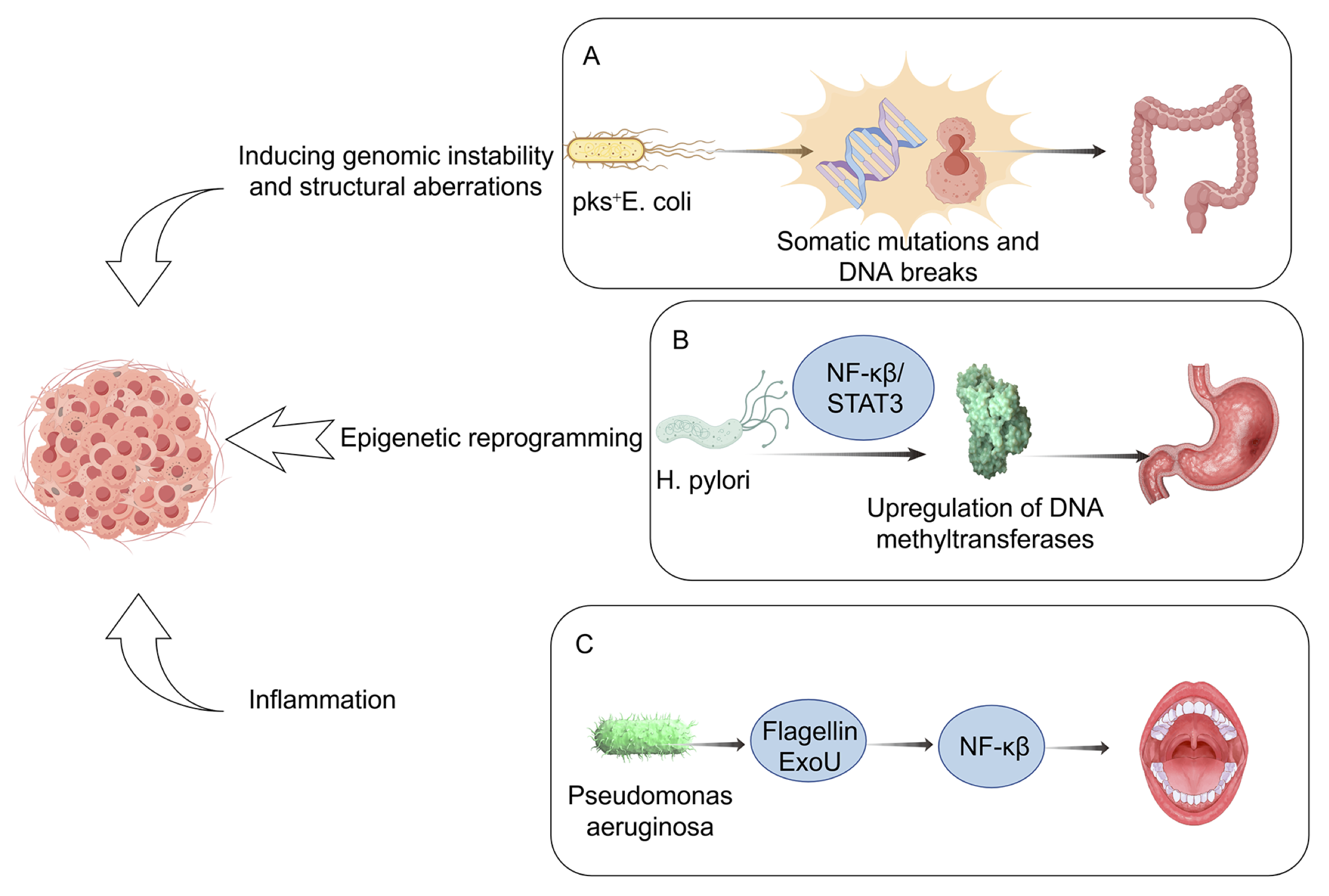

The microbiome contributes to oncogenesis by inducing genomic instability and structural aberrations (23). Within the tumor microenvironment (TME), certain microorganisms and their secreted toxins can directly damage host DNA, thereby increasing the mutational burden in colonized tissues. As DNA lesions accumulate beyond a critical threshold, regulatory networks governing cellular proliferation become disrupted, ultimately driving tumor initiation and progression (24, 25). A well-characterized example is Escherichia coli strains harboring the polyketide synthase (pks) gene cluster (pks⁺E. coli), which has been implicated in colorectal carcinogenesis by inducing somatic mutations and DNA breaks (26, 27) (Figure 2A).

Figure 2. Mechanistic pathways linking the microbiome to cancer development. This schematic summarizes the principal mechanisms through which microbial dysbiosis promotes carcinogenesis. Specific taxa or microbial products may induce DNA damage and genomic instability, trigger chronic inflammation, alter host immune surveillance, and reprogram tumor metabolism. Arrows indicate directional interactions among microbial, immune, and epithelial compartments. The illustration highlights how both commensal and pathogenic microbes can shape the tumor microenvironment, supporting cancer initiation and progression.

In a seminal study, Pleguezuelos-Manzano et al. co-cultured human intestinal organoids derived from healthy stem cells with pks⁺ E. coli, demonstrating that long-term bacterial exposure induces distinctive mutational signatures, including single base substitutions (SBS-pks) and small insertion-deletion events (ID-pks). Beyond bacterial genotoxins, microbial metabolites play a decisive role in promoting DNA damage. For instance, small-molecule derivatives from diverse gut microbiota directly impair DNA integrity in acellular assays, induce double-strand break (DSB) markers (γ-H2AX), and cause epithelial cell-cycle arrest. Specifically, indolimine metabolites from Morganella morganii have been shown to exacerbate colon tumorigenesis in germ-free mice (28). Additional pathogenic mechanisms involve effector proteins secreted by enteropathogenic E. coli and Helicobacter pylori that disrupt DNA mismatch repair, thereby destabilizing the genome and fueling tumorigenesis (29, 30). These processes are frequently associated with the overproduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS), hydrogen sulfide, and nitric oxide, molecules well known to contribute to genotoxic stress (31, 32). Viruses also represent important microbial drivers of genomic instability. For example, Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV) integrates viral DNA into host genomes and persistently expresses the viral T antigen, which contributes to tumorigenesis in approximately 60% of Merkel cell carcinoma cases (33, 34). Beyond genetic alterations, microorganisms exert oncogenic influence through epigenetic reprogramming. H. pylori, particularly CagA-positive strains, can induce aberrant DNA hypermethylation of tumor suppressor gene promoters in gastric mucosa via nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB)/STAT3-mediated upregulation of DNA methyltransferases. Microbe-driven epigenetic modifications, encompassing altered DNA methylation, dysregulated noncoding RNAs, and histone modifications, represent key mechanisms linking chronic infection to malignant transformation (Figure 2B).

Chronic inflammation and the sustained production of inflammatory mediators generate a tumor-permissive microenvironment, thereby constituting a major driver of carcinogenesis (35). Microbial components can act as key inflammatory triggers; for instance, Pseudomonas aeruginosa-derived factors such as flagellin and the cytotoxin ExoU exhibit strong pro-inflammatory activity by recruiting neutrophils and activating NF-κB signaling, ultimately accelerating the progression of oral cancer (36) (Figure 2C). Similarly, disruption of the intestinal epithelial barrier enables microbial products to translocate into host tissues, where they activate tumor-infiltrating dendritic cells (DCs) with inflammatory phenotypes. This, in turn, promotes the polarization of γδ T17 cells, which secrete high levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-17, IL-8, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), and TNF-α. These mediators not only perpetuate inflammation but also recruit polymorphonuclear myeloid-derived suppressor cells (PMN-MDSCs), thereby reprogramming the inflammatory milieu into an immunosuppressive state that facilitates colorectal cancer progression (37). As illustrated in Figure 2, the microbiome influences tumorigenesis through multiple converging axes, including genomic instability, chronic inflammation, immune suppression, and metabolic reprogramming. These pathways interact dynamically within the tumor microenvironment, underscoring the multifactorial nature of microbiome-driven carcinogenesis. The following sections present major cancer types in an order reflecting the progressive spectrum of microbial exposure and research development, from external or mucosal interfaces (e.g., lung and oral cavity) to internal organ systems (e.g., gastrointestinal, hepatic, and endocrine-related malignancies). The sequence aims to illustrate the expanding conceptual framework of microbiome-associated carcinogenesis.

2.1. Lung cancer

Lung cancer ranks as the foremost cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide and represents the second most frequently diagnosed malignancy, representing one of the most frequently diagnosed malignancies (38). The disease is often detected at advanced stages, and its etiology is predominantly linked to tobacco smoking. Nevertheless, epidemiological evidence indicates a rising incidence among never-smokers, now accounting for approximately 25% of cases (39). Biologically, lung cancer is a heterogeneous entity encompassing multiple histopathological subtypes, which are broadly categorized into two principal groups: small-cell lung carcinoma (SCLC), the most aggressive and lethal form, and non-small-cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC) (40). While SCLC accounts for 10-15% of lung cancer cases, approximately 85% are classified as NSCLC, which encompasses three predominant histological subtypes: adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), and large-cell carcinoma, each characterized by distinct histological and molecular profiles. At the molecular level, the genomic architecture and genetic heterogeneity of lung cancer have been extensively delineated, underscoring its nature as a highly heterogeneous group of malignancies. Although recent advances have led to the development of targeted therapies for certain genetic subtypes, the overall survival rate for lung cancer remains alarmingly low. Cigarette smoking remains the primary risk factor, while other well-established contributors include ambient air pollution and occupational exposure to radon and asbestos (41, 42). As the mucosal organ with the largest surface area (e.g., upper vs. lower lobe) and a principal interface between the host and the external environment, the lung is uniquely positioned for continual exposure to airborne microorganisms and environmental pollutants (43,44). However, the precise mechanisms by which these environmental risk factors and other tumor-extrinsic influences drive lung carcinogenesis remain incompletely understood. Traditionally, healthy lungs were thought to be sterile; however, with the advent of increasingly sophisticated detection methodologies, including computed tomography (CT) imaging, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays, and 16S rRNA gene sequencing, investigations into the pulmonary microbiome have expanded considerably (45, 46). Since 2011, growing evidence has highlighted associations between distinct microbial communities and a range of pulmonary pathologies, confirming that they contain a variety of microorganisms (43, 47) (Table 2).

Table 2. Lung microbiome and its association with lung cancer.

| Lung microbiome | Types | Potential mechanisms |

|---|---|---|

| Pseudomonas (47, 49, 57-59) |

Gram-negative, aerobes |

These microbial alterations were found to correlate positively with macrophage abundance and elevated IFN-γ levels in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, as well as with increased neutrophil elastase activity (66, 67). |

| Streptococcus (47, 60-64) |

Gram-positive, facultative anaerobes |

These microbes were shown to upregulate the ERK and PI3K signaling pathways, while exhibiting a negative correlation with active neutrophil elastase levels (68, 69). |

| Sphingomonas (49, 57, 65) |

Gram-negative, strictly aerobes |

They exhibited a positive correlation with macrophage abundance and with IFN-γ levels in the bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL)(66). |

| Propionibacterium |

Gram-positive, facultative anaerobes |

Not Described. |

| Acidovorax |

Gram-negative, aerobes |

Not Described. |

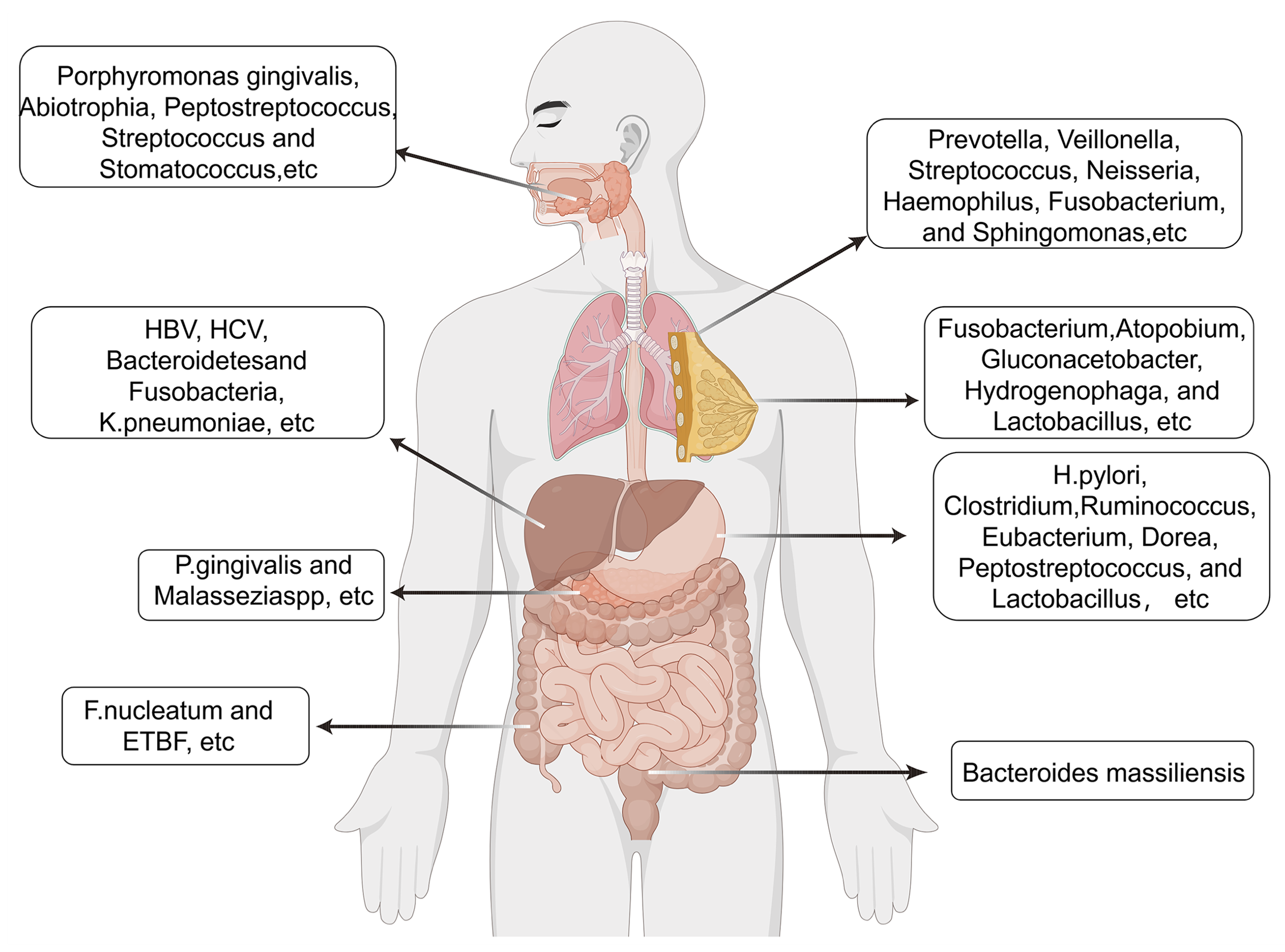

Compositional analyses of the pulmonary microbiome indicate a taxonomic architecture predominantly shaped by the phyla Firmicutes, Proteobacteria, Bacteroidetes, and Actinobacteria. Within this, the airway microbial repertoire encompasses diverse genera, including Prevotella, Veillonella, Streptococcus, Neisseria, Haemophilus, Fusobacterium, Sphingomonas, Pseudomonas, Acinetobacter, Megasphaera, Staphylococcus, and Corynebacterium, which contribute to the ecological complexity and potential functional interactions within the respiratory niche (47-49). Interestingly, marked compositional distinctions exist between the microbiota of the upper and lower respiratory tracts. In healthy individuals, the lower airways are predominantly colonized by Veillonella, Prevotella, and Streptococcus, accompanied by additional taxa such as Fusobacterium and Haemophilus, populations largely derived from the oral microbiome. Mounting evidence underscores the regulatory influence of the gut-lung axis, that is, the gut microbiota modulates pulmonary physiology and immune homeostasis. The intestinal microbiota, comprising a vast array of microbial species, exerts systemic effects on pulmonary immunity through the release of metabolites, microbial ligands, and immune mediators that circulate via the bloodstream. These products not only influence immune activity in the lungs but may also contribute to shaping the composition of the pulmonary microbiome. Conversely, the pulmonary microbial community plays a pivotal role in maintaining respiratory immune homeostasis, engaging in dynamic crosstalk with epithelial and immune cells to orchestrate both innate and adaptive immune responses (50, 51). Recent research has implicated the gut microbiome as a potential mediator linking these environmental exposures to lung tumorigenesis, suggesting that microbial dysbiosis may act in concert with chemical carcinogens to influence disease initiation and progression. Accumulating evidence underscores a strong association between dysbiosis of the gut microbiota and lung cancer. Liu et al. reported reduced microbial diversity and ecosystem stability in lung cancer patients, characterized by the enrichment of opportunistic pathogens and depletion of beneficial taxa (52). Zhuang et al. reported elevated Enterococcus abundance in the gut of lung cancer patients, alongside an overall decline in microbial functionality, suggesting that Enterococcus and Bifidobacterium may serve as potential biomarkers (53). Consistent with this, Zhang et al. observed reduced levels of Kluyvera, Escherichia-Shigella, Dialister, Faecalibacterium, and Enterobacter in lung cancer patients, while Veillonella, Fusobacterium, and Bacteroides were significantly enriched (54). Dysregulation of butyrate-producing bacteria has also been implicated: Gui et al. identified marked reductions in Clostridium leptum, Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Ruminococcus, and Clostridial cluster I spp., whereas Eubacterium rectale and Clostridial cluster XIVa remained unaffected (55). Notably, elevated levels of Bacillus and Akkermansia muciniphila were associated with lung cancer progression (56).

In the context of lung malignancies, distinct microbial signatures have been documented. Accumulating evidence indicates that the pulmonary microbiota can remodel the local immune microenvironment, thereby contributing to tumor progression. In an autochthonous mouse model, Jin et al. provided compelling evidence that crosstalk between the lung microbiota and the host immune system is a critical driver of inflammatory signaling and lung tumorigenesis. They reported that tumor-bearing lungs harbored a distinct microbial signature, characterized by enrichment of taxa such as Herbaspirillum and Sphingomonadaceae. In contrast, healthy lungs were characterized by enrichment of Aggregatibacter and Lactobacillus. Elevated bacterial load and compositional shifts activated Myd88-dependent signaling in myeloid cells, triggering the secretion of IL-1β and IL-23. These cytokines, in turn, expanded and activated Vy6+Vδ1+γδ T cells, which produced IL-17 to amplify inflammation, while concurrently secreting IL-22 and other effector molecules that enhanced tumor cell proliferation. Notably, both germ-free and antibiotic-treated mice exhibited attenuated tumor progression, underscoring that commensal bacteria play an active role in facilitating lung carcinogenesis (70). Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) has been frequently associated with genera such as Klebsiella, Acidovorax, Polaromonas, Rhodoferax, Xylobacter, Eufluobacter, and Clostridium. In contrast, Prevotella and Pseudobutyrivibrio ruminis appear inversely correlated with the disease.

Conversely, non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) has been associated with increased relative abundance of Ruminococcus spp., Akkermansia muciniphila, Eubacterium spp., and Alistipes spp., and reduced prevalence of Bifidobacterium longum, Bifidobacterium adolescentis, and Parabacteroides distasonis. Collectively, these findings suggest that the gut microbiome may exert clinically relevant influences on lung cancer pathogenesis and progression. Although several taxa have been linked to lung cancer, findings are not always consistent across populations, which may reflect differences in diet, geography, and sequencing methods.

2.2. Oral cancer

The origins of oral microbiology can be traced to 1670, when Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, employing a microscope of his own design, first documented the presence of bacteria within the human oral cavity. His meticulous sketches and descriptions of microorganisms exhibiting diverse morphologies provided one of the earliest glimpses into the remarkable complexity of the oral microbial ecosystem (71-73).

Positioned at the forefront of the alimentary tract, the oral cavity sustains a finely tuned microbial equilibrium that underpins both oral and systemic physiological integrity. The oral cavity comprises multiple distinct ecological niches, including the teeth, buccal mucosa, soft and hard palates, and tongue, which together form a highly complex microenvironment. This fosters the coexistence of diverse microbial consortia, collectively referred to as the oral microbiome (74). Oral microbiome dysbiosis is increasingly recognized as a contributing factor in the pathogenesis of a broad spectrum of oral and systemic disorders. Perturbations in this homeostasis, collectively referred to as oral dysbiosis, have been implicated as pivotal contributors to a spectrum of pathological processes. Among these, the intricate and multifaceted interplay between oral microbial dysregulation and oral carcinogenesis has garnered substantial scholarly interest. Notably, malignant transformation within the oral epithelium can actively reshape the resident microbiota, thereby creating a niche increasingly conducive to tumor persistence and progression (75-80).

The term microbiome refers to the collective assemblage of symbiotic, commensal, and pathogenic microorganisms inhabiting a defined ecological niche (81). The oral cavity harbors a vast and diverse array of microorganisms and remains in continuous interaction with the external environment, rendering it particularly susceptible to environmental influences (82). The oral microbiome is a complex consortium of bacteria, fungi, viruses, archaea, and protozoa that collectively contribute to the establishment and maintenance of its normal microbial community (81). Bacteria represent the principal constituents, assembling into habitat-specific microbial consortia across the various niches of the oral cavity.

Investigations into the oral microbiome have identified a remarkable diversity comprising more than 700 bacterial species, which are taxonomically distributed across seven principal phyla: Bacteroidota (Bacteroidetes), Actinomycota (formerly Actinobacteria), Fusobacteriota (Fusobacteria), Bacillota (Firmicutes), Pseudomonadota (Proteobacteria), Spirochaetota (Spirochaetes), and Saccharibacteria. Despite this diversity, most species are derived from only a few dozen genera (83-85). The oral microbiome is characterized by pronounced spatial and temporal variability, exhibiting rapid shifts in both community composition and functional activity that evolve in parallel with host development. These complex, non-equilibrium dynamics arise from a confluence of factors, including dietary components and alterations in local pH, as well as interbacterial interactions that confer novel functional attributes on microbial strains (86). The predominant bacterial taxa that constitute the core of the oral microbiome are conserved primarily across individuals, reflecting a stable and shared microbial framework despite inter-individual variability in less abundant species. The predominant bacterial genera characterizing a healthy oral cavity are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3. Taxonomic profile of the major bacterial genera in the healthy oral microbiome.

| Cocci | Rods | |

|---|---|---|

| Gram positive | Abiotrophia, Peptostreptococcus, Streptococcus, Stomatococcus. | Actinomyces, Bifidobacterium, Corynebacterium, Eubacterium, Lactobacillus, Propionibacterium, Pseudoramibacter, Rothia |

| Gram negative | Moraxella, Neisseria, Veillonella | Campylobacter, Capnocytophaga, Desulfobacter, Desulfovibrio, Eikenella, Fusobacterium, Hemophilus, Leptotrichia, Prevotella, Selemonas, Simonsiella, Treponema, Wolinella. |

Beyond bacterial populations, the oral microbiota also comprises diverse microeukaryotes, such as fungi, amoebae, and flagellates, as well as archaeal species and a broad spectrum of viruses (87). In most individuals, the oral mycobiome is composed primarily of fungal species belonging to the genera Candida and Malassezia (88-93). The oral microbiota exerts a pivotal influence on oral health, as three of the most common oral pathologies, dental caries, periodontal disease, and oral cancer, are primarily driven by microbial etiologies. Several extensively characterized periodontal microbiomes have been identified as central to elucidating the mechanistic links between oral microbial dysbiosis and oncogenesis (94). Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) represents the predominant malignancy of the head and neck region, comprising nearly 2% of all cancer diagnoses worldwide (95). While traditionally linked to lifestyle risk factors such as tobacco use and excessive alcohol consumption, emerging evidence implicates specific constituents of the oral microbiome in OSCC pathogenesis. Among these, Porphyromonas gingivalis has garnered particular attention, given its well-documented association with both the initiation and progression of neoplastic transformation within the oral cavity (96). In a comparative analysis of microbial communities within OSCC lesions and contralateral healthy tissues from 50 patients, Zhang et al. reported a significant enrichment of Porphyromonas species in tumor-associated samples (97). This observation is consistent with findings by Katz et al., who documented elevated levels of P. gingivalis in gingival specimens from patients with OSCC compared with healthy controls (98). Together, these studies underscore that microbial communities differ markedly between malignant and adjacent healthy oral tissues, with tumor sites harboring a greater abundance of pathogenic taxa. A systematic review and meta-analysis by Sayehmiri et al. further confirmed this association (99), revealing that colonization by P. gingivalis was associated with an increased risk of oral cancer (odds ratio, 1.36), with gingival cancers accounting for most cases. Experimental evidence also supports these observations: in a murine model, Wen et al. demonstrated that P. gingivalis infection promoted tumor multiplicity and growth and accelerated malignant progression (100). Beyond P. gingivalis, Rai et al. recently demonstrated that Porphyromonas endodontalis was also enriched in the salivary microbiota of patients with OSCC, suggesting that multiple Porphyromonas species may contribute to oral tumorigenesis (101).

As the lungs and oral cavity are connected, the composition and dynamics of the oral microbiome are closely linked to those of the lung microbiome. Migration of oral bacteria into the lower respiratory tract represents a key pathogenic mechanism underlying aspiration pneumonia (102). Likewise, their colonization of the gastrointestinal tract, often intensified by dysregulated gastric or bile acid secretion in systemic disorders such as cirrhosis, has been associated with the development of inflammatory bowel disease and colorectal cancer (103-107).

In addition, the carriage of specific oral microbiota has been linked to an increased susceptibility to pancreatic cancer (PC) (108-111). Multiple studies have reported significant associations between Porphyromonas gingivalis and PC, while Mitsuhashi et al. demonstrated that the intratumoral presence of Fusobacterium nucleatum correlates with poorer clinical outcomes (112). Beyond these organisms, Fan et al. further identified Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans and Alloprevotella as associated with an increased risk of PC development (108. Moreover, Wei et al. reported that colonization by Leptotrichia and Streptococcus species is also associated with an elevated risk of pancreatic cancer (113). In one of the earliest investigations into the association between the oral microbiota and PC, Farrell et al. identified an enrichment of Granulicatella adiacens in patients with PC. Additionally, their analysis revealed differential abundances of Neisseria elongata and Streptococcus mitis between affected individuals and healthy controls (114). It remains uncertain whether these microbes are true oncogenic drivers or secondary colonizers of the tumor niche.

2.3. Gastric cancer

Gastric cancer (GC) ranks among the most prevalent malignancies and remains a leading contributor to global cancer-related mortality (115, 116). GC was initially categorized based on histopathological and anatomical criteria; however, these conventional classifications proved inadequate for guiding therapeutic decision-making and yielded only a slight improvement in patient outcomes. More recently, clinical and molecular profiling has emerged as a more reliable framework for stratifying patients and tailoring treatment strategies. Genomic approaches have been particularly instrumental in delineating molecular subtypes of GC. In 2011, Tan et al. proposed two distinct genomic variants-the genomic intestinal (G-INT) and genomic diffuse (G-DIF) subtypes, characterized by unique histological features, gene expression signatures, biological pathways, and prognostic implications. These molecular subtypes partially overlap with Lauren’s traditional classification, reflecting the profound clinical and biological heterogeneity inherent to GC, mainly attributable to the diverse molecular landscapes of malignant cells (117). GC is rarely diagnosed at an early stage, which substantially restricts therapeutic options. Its biological complexity continues to obscure a comprehensive understanding of disease mechanisms, thereby posing significant challenges to effective management and eradication. The development of GC represents the culmination of a multifaceted interaction among host genetic susceptibilities, environmental exposures such as tobacco use, alcohol consumption, high dietary salt and meat intake, and insufficient consumption of fruits and vegetables, and microbial influences, most notably Helicobacter pylori infection and alterations within the gastric microbiome (118-120). A defining feature of GC lies in its intricate relationship with the resident microbial ecosystem of the stomach. While Helicobacter pylori has long been established as the primary initiator of gastric carcinogenesis, emerging evidence highlights the broader contribution of diverse microbial inhabitants of the gastric mucosa to disease progression (121). Perturbations in the gastric microbiota appear to orchestrate key events across the carcinogenic continuum, spanning the transition from premalignant alterations to the establishment of invasive gastric cancer (122-125).

The human gastrointestinal tract harbors a highly diverse microbial ecosystem, collectively referred to as the gut microbiome. This community is primarily composed of four dominant bacterial phyla: Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria, and Proteobacteria. Among these, Firmicutes, including genera such as Clostridium, Ruminococcus, Eubacterium, Dorea, Peptostreptococcus, and Lactobacillus, are the most prevalent, accounting for approximately 30.6%-83% of the total microbiota. Bacteroidetes, primarily represented by Bacteroides, constitute 8-48%, whereas Actinobacteria, dominated by Bifidobacterium, contribute 0.7-16.7%. Proteobacteria, including members of the Enterobacteriaceae, make up a variable fraction ranging from 0.1-26.6% (126). Alterations in microbial composition can impair the equilibrium between the gut microbiota and the host immune system, thereby predisposing the intestinal environment to chronic inflammation and subsequent oncogenic transformation.

Extensive research has established Helicobacter pylori as a central factor in gastric cancer (GC) pathogenesis. Its discovery not only overturned the long-standing belief that the acidic stomach is sterile but also marked the identification of the only bacterial species thus far classified as a class I carcinogen. Although spiral-shaped microorganisms in the stomach had been observed earlier, it was not until 1982 that Warren and Marshall conclusively linked bacterial infection to chronic gastritis and successfully isolated the causative organism (127, 128). The gastric environment exhibits a steep pH gradient, ranging from 1 to 2 within the gastric lumen to 6 to 7 along the mucosal surface, with the latter providing a more favorable niche for microbial colonization (129, 130). Bacteria typically enter the stomach from the upper digestive or respiratory tracts. Among these, Helicobacter pylori has uniquely adapted to survive in the acidic milieu of the stomach and is recognized as a key etiological agent of noncardiac gastric adenocarcinomas. This Gram-negative, spiral-shaped, flagellated member of the phylum Proteobacteria exhibits urease, catalase, and oxidase activities, which facilitate its persistence in the gastric niche (131, 132). H. pylori is characterized by high motility conferred by a unipolar bundle of sheathed flagella (133). Clinically, H. pylori infection is strongly implicated in the pathogenesis of chronic gastritis, atrophic gastritis, mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma, and gastric adenocarcinoma (134).

H. pylori promotes gastric carcinogenesis by inducing direct genotoxic stress, primarily through the conversion of nitrogenous compounds in gastric fluid into carcinogenic N-nitroso compounds (NOCs) and reactive nitrogen intermediates, while simultaneously fostering a chronic pro-inflammatory microenvironment within the gastric mucosa (135). The oncogenic potential of H. pylori is largely attributed to two major virulence determinants: cytotoxin-associated gene A (CagA) and vacuolating cytotoxin A (VacA), which perturb host cell functions and activate oncogenic signaling pathways (136, 137). CagA, a strain-specific effector protein delivered into host epithelial cells via the H. pylori type IV secretion system, functions as a classical oncogene. Its activity contributes to chronic gastritis, peptic ulcer disease, MALT lymphoma, and gastric carcinoma. Mechanistically, CagA disrupts epithelial homeostasis by suppressing apoptotic pathways and inducing morphological abnormalities, such as cell scattering, elongation, and loss of polarity (137). VacA represents another major H. pylori virulence determinant, functioning as a multifunctional exotoxin that induces diverse pathological effects in host cells, including vacuolization, apoptosis, and necrosis. Beyond these cytotoxic properties, VacA integrates into host cell membranes, where it behaves as an anion-selective channel. Through this channel activity, VacA facilitates the efflux of bicarbonate and organic anions into the cytoplasm, which enhances H. pylori colonization and persistence within the gastric niche (138). H. pylori infection elicits chronic inflammation within the gastric mucosa, a recognized antecedent of neoplastic transformation (139). H. pylori also induces inflammatory responses in gastric epithelial cells primarily through activation of NF-κB, which drives the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines, including interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-2, IL-6, IL-7, IL-8, IL-10, interferon-γ (IFN-γ), and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α). In addition, H. pylori promotes inflammation by upregulating cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), thereby increasing prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) production (139).

Accumulating evidence indicates that, beyond H. pylori, other constituents of the gastric microbiota play critical roles in driving malignant transformation. For example, fungi and viruses may also contribute to the multifactorial processes underlying gastric carcinogenesis. A study by Zhong M et al. identified a GC-associated mycobiome imbalance characterized by disrupted fungal composition and ecology, highlighting Candida albicans as a potential fungal biomarker for gastric cancer. In GC samples, the relative abundance of C. albicans, Fusicolla acetilerea, Arcopilus aureus, and Fusicolla aquaeductuum was markedly elevated, whereas Candida glabrata, Aspergillus montevidensis, Saitozyma podzolica, and Penicillium arenicola were significantly reduced. Moreover, C. albicans may contribute to gastric carcinogenesis by reducing fungal richness and diversity in the stomach, thereby facilitating disease progression (13). Fungal dysbiosis in the stomach has been shown to activate inflammatory pathways, including cytokine and chemokine signaling. In the context of impaired immune responses, particularly in patients with advanced-stage GC, this imbalance increases susceptibility to opportunistic fungal infections. However, whether the enrichment of specific fungi in GC is a driving factor in immune dysregulation or merely a consequence of tumor-associated changes remains unresolved, and their potential roles as oncogenic pathogens warrant further investigation (140, 141). Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) accounts for approximately 7-9% of global gastric cancer cases annually and promotes carcinogenesis through extensive genomic and epigenomic alterations (142). EBV-driven amplification and overexpression of programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) enable tumor cells to evade T cell-mediated immunity, while latency-associated products, including EBV nuclear antigen 1, latent membrane protein 2A, and viral microRNAs, further contribute to oncogenesis by inducing epigenetic dysregulation and aberrant mRNA transcription (143, 144). Although other viruses, such as human papillomavirus, human herpesvirus, and hepatitis viruses, have been implicated in GC, no definitive causal role has been established. Overall, the gastric virome remains poorly characterized and warrants further investigation (145).

2.4. Pancreatic cancer

Pancreatic cancer (PC) represents one of the most lethal and aggressive malignancies, with a rising incidence globally. In the United States, the current 5-year overall survival rate remains dismal at only 10.8%. Broadly, pancreatic cancers are classified into two major categories: pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) constitutes over 90% of all pancreatic malignancies, representing the predominant histological subtype (146), and pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PanNETs), a less common but biologically distinct entity (147). PDAC is a highly aggressive malignancy characterized by an exceptionally poor prognosis. This unfavorable outcome is primarily attributed to its frequent diagnosis at advanced, often unresectable stages, coupled with a high degree of intrinsic and acquired resistance to conventional therapies. Surgical resection remains the sole potentially curative treatment for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma; however, only approximately 20% of patients present with tumors amenable to resection at the time of diagnosis (148). Despite intensive research, the molecular mechanisms driving PDAC oncogenesis and its profound treatment refractoriness remain incompletely understood (149). The development of pancreatic cancer is driven by a multifactorial interplay of influences, including genetic alterations, lifestyle factors, particularly smoking and high-fat diets; dysbiosis of the gut microbiota; and comorbid conditions such as obesity, type 2 diabetes, and chronic pancreatitis, among others (150-154). Given the poor long-term outcomes of PDAC and the limited efficacy of current systemic therapies, there is an urgent need to develop novel therapeutic approaches and supportive strategies that aim to improve patients' quality of life. Increasing attention has recently been directed toward the relationship between pancreatic cancer and the microbiome. In PDAC, dysbiosis involving bacterial, fungal, and viral communities has been consistently reported (155). Thus, modulation of the gut microbiome and restoration of its ecological balance may represent a promising avenue for therapeutic intervention.

Historically, the pancreas was regarded as a sterile organ, much like the lung. However, recent advances in sequencing technologies have revealed that pancreatic tissue harbors its own distinct microbiota (156). In a seminal study, Pushalkar et al. used 16S rRNA gene sequencing and demonstrated that Proteobacteria, Bacteroidetes, and Firmicutes were significantly enriched in pancreatic cancer tissue compared with normal pancreatic tissue (157). Accumulating evidence now suggests that the intratumoral microbiome plays a crucial role in the initiation, progression, and prognosis of pancreatic cancer (154, 157-161). These effects are mediated mainly by microbial modulation of host immune responses and by alterations in drug metabolism, thereby influencing both tumor biology and therapeutic outcomes. Multiple epidemiological and mechanistic studies have highlighted the contribution of periodontal disease and tooth loss to pancreatic carcinogenesis. A comprehensive meta-analysis reported a strong association between periodontal pathologies, particularly the presence of Porphyromonas gingivalis, and increased risk of pancreatic cancer (162). Furthermore, several investigations have explored the relationship between specific oral pathogens, including P. gingivalis, Fusobacterium spp., Neisseria elongata, and Streptococcus mitis, and the development of PDAC. Among these, P. gingivalis consistently shows the strongest positive correlation with PDAC susceptibility, suggesting a potential role as a microbial risk factor in pancreatic tumorigenesis (163, 164). Emerging evidence indicates that fungal and viral infections may contribute to the pathogenesis of pancreatic cancer (PC).

A study by Aykut et al. demonstrated that the intrapancreatic mycobiome, particularly enriched with Malassezia spp., is closely associated with the development and progression of PDAC. The fungal composition of tumor tissue was distinct from that of the gut or normal pancreatic tissue. Notably, experimental ablation of the mycobiome suppressed tumor growth in both slowly progressive and invasive murine PDAC models, whereas repopulation with Malassezia spp. accelerated oncogenesis. Mechanistic investigations revealed that ligation of mannose-binding lectin (MBL), which recognizes glycans on the fungal cell wall and activates the complement cascade, is essential for this tumor-promoting effect (154). Additional evidence links Candida infection with pancreatic cancer risk. A prospective cohort study in Sweden identified an association between oral Candida colonization and an increased incidence of PC (165). Mechanistically, Candida may drive tumorigenesis by inducing chronic inflammation and promoting the expansion of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), thereby fostering an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (150). Viruses have also been implicated in pancreatic carcinogenesis. Several studies have reported associations between chronic pancreatitis and hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, while a meta-analysis by Arafa et al. demonstrated that hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection significantly increases the risk of PC (166-168). These findings suggest that chronic viral infections, through persistent inflammation and pancreatic injury, may serve as cofactors in pancreatic tumorigenesis. Collectively, these studies highlight the potential oncogenic roles of fungi and viruses in PC, warranting further mechanistic and clinical investigations.

2.5. Colorectal cancer

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the most prevalent malignancy of the digestive tract and represents a major global health burden. Accounting for approximately 10% of all cancer diagnoses, CRC is currently the third most common cancer worldwide and ranks among the leading causes of cancer-related mortality. Recent estimates indicate nearly 700,000 deaths annually, underscoring its persistently high morbidity and mortality rates. While CRC was considered relatively uncommon several decades ago, its incidence has risen sharply, making it one of the most lethal cancers globally (95, 169). The global burden of colorectal cancer is exacerbated not only by demographic transitions, such as population ageing, and the prevalence of Westernized dietary habits, but also by modifiable lifestyle determinants, including obesity, sedentary behavior, and tobacco use. Collectively, these factors amplify disease incidence and mortality, rendering colorectal cancer a formidable challenge to healthcare systems across the world (170).

The gut microbiome has increasingly been recognized as a pivotal determinant in human health and disease, with mounting evidence highlighting its relevance in CRC. Numerous investigations have demonstrated that alterations in microbial composition, shaped by dietary patterns and environmental exposures, can promote CRC development through mechanisms involving chronic inflammation, bioactive microbial metabolites, and pathogenic virulence factors. Beyond tumor initiation, dysbiosis of the gut microbiota also exerts a profound influence on CRC progression and trajectory (170-172). Fusobacterium nucleatum has emerged as one of the most extensively studied bacterial taxa implicated in colorectal carcinogenesis. Metagenomic profiling consistently associates Fusobacterium spp. with CRC, although the precise nature of this relationship, causal or correlative, remains unresolved. Castellarin et al. reported a nearly 400-fold increase in F. nucleatum transcript levels in CRC tissues relative to adjacent normal mucosa, underscoring its enrichment in the tumor microenvironment. In an (APC)+/− mouse model, F. nucleatum promoted neoplastic progression by creating a pro-inflammatory milieu within intestinal epithelial cells and facilitating the recruitment of tumor-infiltrating immune cells (173, 174). Elevated IL-17a expression has also been observed in CRC patients with abundant F. nucleatum, suggesting a role in inflammation-driven tumorigenesis. Mechanistically, this strain exhibits strong mucosal adherence and produces Fusobacterium adhesin A (FadA), a virulence factor that binds to E-cadherin and activates β-catenin signaling, thereby driving oncogenic pathways (175, 176). Notably, F. nucleatum has been associated with consensus molecular subtype 1 (CMS1) CRC, characterized by microsatellite instability and immune pathway upregulation (177, 178). More recently, studies of metastatic CRC demonstrated that nearly identical strains of Fusobacterium persist in both primary tumors and distant metastases, highlighting its potential role as a stable component of the tumor microenvironment and a facilitator of disease dissemination (179).

Enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis (ETBF), a strain that produces B. fragilis toxin (BFT), is implicated not only in diarrheal disease and inflammatory bowel disease but also in colorectal tumorigenesis (180, 181). Mechanistically, ETBF promotes tumor development by activating STAT3 signaling and driving a Th17-mediated inflammatory response (182). Colonization with BFT+ B. fragilis also promotes the accumulation of regulatory T cells, thereby amplifying IL-17-driven procarcinogenic inflammation (183). In epithelial cells, BFT induces cleavage of E-cadherin, thereby increasing paracellular permeability and activating β-catenin signaling, ultimately enhancing proliferative capacity (184). Beyond direct host signaling, BFT+ B. fragilis perturbs the gut microbial ecosystem by fostering dysbiosis, encouraging the outgrowth of other procarcinogenic taxa, impairing mucosal immune defenses, disrupting epithelial barrier integrity, and promoting mucin degradation (183-186).

Pathogenic Escherichia coli harboring the pks genomic island represents another gut-associated bacterium that is strongly enriched in CRC tissues and is functionally linked to tumor promotion in preclinical models. Strains carrying the pks island secrete a family of heat-labile cytolethal distending toxins that colonize the intestinal mucosa, elicit inflammation, and increase the host's mutational burden (187). Moreover, pks⁺ E. coli encodes the genotoxic polyketide-peptide hybrid colibactin, which, upon delivery to eukaryotic cells, induces DNA double-strand breaks, disrupts the cell cycle, and generates chromosomal abnormalities. These combined mutagenic and pro-inflammatory effects establish pks⁺ E. coli as a potent microbial driver of colorectal tumorigenesis (20, 188).

Among tumor-associated microbes, Fusobacterium nucleatum and pks⁺ Escherichia coli are among the most intensively studied species. Both contribute to colorectal tumorigenesis through intertwined mechanisms of inflammation, genotoxicity, and immune modulation (187). F. nucleatum promotes chronic inflammation by activating the NF-κB pathway and inducing cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α. Its adhesin, FadA, facilitates β-catenin signaling, thereby enhancing epithelial proliferation, whereas its Fap2 protein binds to TIGIT on T cells and NK cells, leading to promoting immune evasion. Conversely, pks⁺ E. coli produces colibactin, a genotoxin that causes DNA double-strand breaks and generates a characteristic mutational signature identified in human colorectal tumors (187). Despite compelling mechanistic data, the exact oncogenic role of these microbes remains a matter of controversy. Some studies suggest that F. nucleatum colonizes pre-existing lesions rather than initiating cancer, whereas others show that its depletion reduces tumor burden in animal models. Similarly, colibactin’s genotoxicity is context-dependent, varying with host DNA-repair capacity and microbial abundance. Furthermore, both bacteria can reshape the tumor microenvironment, either by amplifying inflammation or promoting immunosuppression, depending on tumor stage and host immunity. Integrating these findings suggests that F. nucleatum and pks⁺ E. coli act not as single “drivers,” but as dynamic modulators within the complex microbial ecosystem, influencing tumor evolution.

2.6. Hepatocellular carcinoma

Globally, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is recognized as a highly prevalent malignancy and a foremost cause of cancer mortality (189, 190). Major etiological factors include persistent infection with the hepatitis B virus (HBV) or the hepatitis C virus (HCV), alcoholic liver disease, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). These conditions drive progressive hepatic injury and fibrogenesis, culminating in cirrhosis, which constitutes the principal precursor state for HCC development (191).

Gut microbiome dysbiosis is a characteristic feature of patients with HCC, typically characterized by an expansion of pathogenic taxa and a depletion of commensal, health-promoting bacteria. In a study by Zhang et al., hepatocellular carcinoma patients stratified by the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer staging system exhibited progressive alterations in gut microbiota composition, characterized by increased abundances of Enterococcus and Enterobacteriaceae and concomitant reductions in Actinobacteria and Bifidobacterium, with advancing disease severity (192). In a study conducted by Zheng et al., comparative analysis across cohorts of patients with hepatitis, cirrhosis, cirrhosis-associated HCC, non-cirrhosis-related HCC, and healthy controls revealed that HCC patients exhibited a significant enrichment of Bacteroidetes and Fusobacteria, along with increased gut microbial diversity relative to the other groups (193). Wang et al. provided compelling evidence for a causal role of gut dysbiosis in hepatocarcinogenesis. Using fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) from patients with HCC and healthy controls into germ-free and specific-pathogen-free (SPF) mice, they demonstrated that reconstitution with HCC-associated microbiota induced spontaneous liver inflammation, fibrosis, and dysplasia, and accelerated chemically induced HCC. Mechanistically, HCC-derived microbiota disrupts intestinal barrier integrity, facilitating the translocation of viable pathogenic bacteria into the liver and triggering pro-inflammatory cascades that sustain tumorigenesis. Notably, both murine and human livers showed enrichment of Klebsiella pneumoniae, and monocolonization with this species recapitulated the tumor-promoting effects of HCC-FMT, thereby establishing K. pneumoniae as a key oncogenic driver in HCC (194). Moreover, the dynamic crosstalk between bile acids (BAs) and the gut microbiota has emerged as a pivotal determinant in the initiation and progression of HCC. Under physiological conditions, BA metabolism is tightly orchestrated through bidirectional interactions between host and microbial communities, whereby gut microorganisms modulate BA composition and BAs act as signaling molecules to preserve hepatic and intestinal homeostasis. However, dysbiosis of the gut microbiota in chronic liver disease and malignant transformation perturbs BA equilibrium, thereby fostering hepatic inflammation and fibrogenesis and ultimately driving hepatocarcinogenesis (195).

The liver maintains a tightly interconnected bidirectional communication with the gut microbiota, commonly referred to as the gut-liver axis. Microbial communities and their metabolites exert a profound influence on hepatic homeostasis, while the disruption of this equilibrium, termed dysbiosis, has been implicated in the pathogenesis of diverse liver disorders (196, 197). Mechanistically, microbial dysbiosis promotes hepatic injury and inflammation by compromising intestinal barrier integrity, thereby facilitating bacterial translocation and exposure of the liver to microbial products and pathogen-associated molecular patterns. For instance, studies have demonstrated that elevated systemic levels of zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1), a tight junction protein, correlate with increased intestinal permeability, heightened inflammatory responses, and greater disease severity in patients with HCC (198, 199). Disruption of intestinal barrier integrity permits the translocation of microbial products, most notably lipopolysaccharide (LPS), thereby delivering potent pro-inflammatory cues from the gut lumen directly into the hepatic milieu (197, 198, 200, 201). LPS engages toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), triggering the downstream activation of the NF-κB signaling cascade and the consequent secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Under conditions of dysbiosis, bacterial overgrowth exacerbates the TLR4-NF-κB-mediated inflammatory axis, thereby fostering persistent intestinal inflammation and driving hepatocarcinogenesis (202, 203).

2.7. Breast cancer

Breast cancer (BC) is the most frequently diagnosed malignancy among women and, despite considerable advances in diagnostic approaches and therapeutic strategies, it continues to rank as a leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide (204). Breast cancer represents a heterogeneous malignancy comprising distinct subtypes with unique epidemiological features (205). Globally, it accounts for approximately one-third of all cancers diagnosed in women, with mortality contributing to nearly 15% of cases (206, 207). A multifactorial interplay of genetic predisposition, environmental exposures, and lifestyle determinants shapes the worldwide distribution of breast cancer. While incidence rates are typically higher in high-income countries, mortality is comparatively lower due to the availability of early detection programs and more effective therapeutic interventions, in contrast to resource-limited settings (208). In recent years, the microbiome has emerged as a novel factor potentially linked to BC. As a fundamental regulator of human health and homeostasis, the microbiome exerts broad effects on biological, hormonal, and metabolic pathways. Through these mechanisms, it may influence tumor initiation, proliferation, and genomic instability in host cells, whereas in other contexts it can promote apoptosis and tumor suppression (209, 210).

Complementary work by Smith et al. revealed that the breast tissue microbiome exhibits variability across racial groups, tumor stages, and molecular subtypes, underscoring its potential role in shaping disease heterogeneity (211). In a large cohort study, Thompson et al. demonstrated a significant association between the breast microbiota and host gene expression, identifying bacterial taxa that correlated with molecular programs governing epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and cellular proliferation. More recent investigations have further highlighted the functional importance of intratumoral microbiota, demonstrating that these microorganisms facilitate breast cancer metastasis by enhancing cellular resistance to fluid shear stress through actin cytoskeletal remodeling, thereby promoting tumor cell survival and dissemination (212). Collectively, these findings underscore that intratumoral microorganisms are not merely incidental but are pervasive within breast cancer tissues, where they may actively influence disease initiation, progression, and clinical outcome.

Multiple studies have demonstrated that the microbial composition of mammary gland tissue undergoes distinct alterations between malignant and non-malignant states, as well as across different tumor stages (213, 214). Xuan et al. identified Sphingomonas yanoikuyae as a commensal organism in normal breast tissue, which was markedly depleted in tumor samples. At the same time, Methylobacterium radiotolerans emerged as the most significantly enriched bacterium within tumor tissue (215). In an Asian breast cancer cohort, tumor tissues were found to harbor increased abundances of Propionicimonas, Micrococcaceae, Caulobacteraceae, Rhodobacteraceae, Nocardioidaceae, and Methylobacteriaceae, accompanied by a reduction in Bacteroidaceae (216). Notably, disease progression was associated with a concomitant enrichment of the genus Agrococcus. Furthermore, advanced malignancy was associated with increased prevalence of Fusobacterium, Atopobium, Gluconacetobacter, Hydrogenophaga, and Lactobacillus, highlighting a progressive remodeling of the breast tumor microbiome in relation to oncogenesis (217).

Endogenous estrogen plays a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of breast cancer, particularly in the postmenopausal setting, where approximately 70% of tumors are classified as estrogen receptor positive. Before menopause, the ovaries serve as the primary site of estrogen biosynthesis, and circulating estrogens exert systemic endocrine effects on various target tissues, including the skeletal, neural, and immune systems (218). Following hepatic metabolism, estrogens and their derivatives undergo conjugation via glucuronidation and sulfonation, processes that facilitate their excretion through bile. Although a substantial fraction of these conjugated metabolites is eliminated in urine and feces, a considerable proportion undergoes enterohepatic recirculation. This is mediated by gut microbes that express β-glucuronidase activity, which hydrolyze conjugated estrogens to their bioactive forms, thereby facilitating reabsorption into the systemic circulation. Moreover, intestinal microorganisms can generate estrogenic compounds or structural mimics from dietary substrates, further influencing host estrogen homeostasis (218). β-glucuronidase is a central enzymatic component of the estrobolome, deconjugating estrogens and thereby restoring their bioactive forms for reabsorption into the systemic circulation.

Recent work refines the “estrobolome” concept, the ensemble of gut-microbial genes (notably β-glucuronidases) that deconjugate hepatically conjugated estrogens excreted in bile, thereby enabling enterohepatic reabsorption and altering systemic estrogen exposure relevant to ER⁺ disease. Contemporary reviews map estrobolome enzymatic targets/taxa and propose standardized measurement panels to align microbiome endpoints with breast cancer risk and therapy studies (219, 220). Large 2024-2025 syntheses and narrative updates collectively report links between gut/breast microbial signatures and tumor risk, subtype, and treatment response, yet emphasize heterogeneity across cohorts and the current inability to meta-analyze genera consistently associated with outcomes (Table 4).

Table 4. Recent updates (2024-2025) for breast and prostate microbiome research.

| Domain | Key 2024-2025 insights | Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Breast - Estrobolome and estrogen | Estrobolome targets mapped; β-glucuronidase-mediated deconjugation drives enterohepatic estrogen recycling; tissue and multi-kingdom signals revisited with stricter controls. | Align microbiome endpoints with ER⁺ risk/therapy; prioritize standardized assays for Estrobolome activity. |

| Breast - Evidence synthesis | 2025 systematic review: 48 studies; heterogeneity precludes genus-level meta-analysis; stool and tissue datasets dominate; need for harmonized pipelines. | Standardize sampling/bioinformatics; design longitudinal/interventional studies. |

| Prostate - Urinary microbiome | Reviews emphasize urinary/tissue microbiomes as non-invasive biomarkers, methodology standardization outstanding. | Develop validated urine microbiome pipelines for screening and risk stratification. |

| Prostate - Gut - prostate axis and hormones | Gut microbes can influence androgen pathways and ADT response; lower α-diversity correlates with tumor burden; cross-species models support hormonal crosstalk. | Integrate microbiome-hormone multi-omics; test microbial modulation alongside hormonal therapy. |

2.8. Prostate cancer

Prostate cancer (PCa) represents the second most frequently diagnosed malignancy in men worldwide. It remains a leading cause of cancer-related mortality, accounting for approximately 1.6 million new cases and 366,000 deaths each year (221, 222). Epidemiological and observational studies provide compelling evidence that unhealthy dietary patterns, excessive alcohol intake, and tobacco use are strongly associated with an elevated risk of chronic non-communicable diseases, including various malignancies (223). Nonetheless, the precise contribution of these lifestyle factors to prostate cancer (PCa) pathogenesis remains inconclusive. Emerging evidence has increasingly underscored the role of the human microbiota, particularly the gut microbiota (GM), in shaping disease susceptibility and progression. As a result, microbial communities residing in the gut have garnered considerable attention for their potential influence on host physiology and their implications in PCa development (224, 225). In 2018, Liss et al. analyzed the gut microbiota in 133 American men undergoing prostate biopsy and, for the first time, demonstrated a potential association between the gut microbiome and prostate cancer (226). In a separate study, Bacteroides massiliensis was found to be more prevalent in the gut microbiota of Caucasian men with prostate cancer compared to those with benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). In contrast, Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and Eubacterium rectalis were observed at reduced levels (227).

The gut microbiota has recently been conceptualized as an androgen-producing “organ.” Emerging evidence indicates that microbial metabolites can influence prostate cancer growth and progression, supporting the existence of a “gut-prostate axis” (228). Androgens are central drivers of prostate cancer, exerting their effects through binding to the androgen receptor in malignant prostate cells. While testosterone is primarily synthesized in the testes and dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) in the adrenal glands (229), several studies suggest that the gut microbiota also contributes to androgen biosynthesis and regulation, thereby potentially shaping the hormonal milieu that governs prostate cancer development. Matsushita M et al. collected rectal swab samples from Japanese male subjects who were clinically suspected of having prostate cancer and underwent prostate biopsy. To minimize confounding factors, individuals with positive biopsy results were excluded, ensuring that only patients without prostate cancer were included in the analysis. In this cohort of elderly men, we investigated the association between gut microbiota composition and circulating testosterone levels. Microbial community diversity, assessed using both α- and β-diversity indices, did not differ significantly by testosterone status. However, taxonomic profiling revealed that specific genera within the phylum Firmicutes were more prevalent in subjects with higher total testosterone (TT) levels.

Notably, beyond gut dysbiosis, recent studies have profiled the urinary and prostate-tissue microbiomes as potential noninvasive biomarkers for early detection and risk stratification (230). Reviews summarize that distinct urinary/gut consortia correlate with incidence, grade, and treatment outcomes; however, causality remains unresolved, and standardization is needed for specimen collection, sequencing, and batch control (Table 3). Mechanistically, the gut-prostate axis encompasses microbial effects on androgen metabolism (e.g., steroidogenic pathways and 5α-reductase activity), immune tone, and tumor energetics, features implicated in castration resistance and response to androgen-deprivation therapy (ADT). Longitudinal translational work reports that reduced fecal α-diversity correlates with tumor burden in hormonotherapy-naïve PCa, and that microbial community shifts may modulate hormonal treatment responses. Parallel reviews call for integrated multi-omics and prospective designs to resolve directionality and identify therapeutic leverage points.

2.9. Gynecological cancers

Cervical cancer ranks as the fourth most prevalent malignancy among women, accounting for an estimated 342,000 deaths in 2020. More than 95% of cases are attributable to persistent infection with human papillomavirus (HPV), a pathogen with exceptionally high prevalence, as over 70% of sexually active women are estimated to acquire infection during their lifetime (231, 232). Histologically, cervical cancer is predominantly classified into two subtypes: squamous-cell carcinoma (SCC), which constitutes the majority, and adenocarcinoma (ADC) (233). Increasing evidence indicates that the vaginal microbiota exerts a significant influence on both cervical carcinogenesis and the persistence or clearance of HPV. Brotman, R. M., et al. have reported that Lactobacillus gasseri abundance correlates with viral clearance, whereas Atopobium spp. is strongly associated with HPV persistence (234). Moreover, the vaginal microbiota of women with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia or cervical cancer is characterized by marked depletion of Lactobacillus spp. compared to healthy counterparts, alongside enrichment of taxa frequently linked to bacterial vaginosis, including Gardnerella, Megasphaera, Prevotella, Peptostreptococcus, Streptococcus, Sneathia sanguinegens, and Atopobium. These microbial shifts suggest a dysbiotic microenvironment that may facilitate viral persistence and malignant transformation (235).

Endometrial cancer (EC), arising from the epithelial lining of the uterine cavity, represents a malignancy with steadily increasing incidence and associated mortality worldwide. Traditionally, EC has been stratified into two broad categories. Type I tumors are predominantly driven by unopposed estrogen exposure, are typically low-grade, more frequently encountered, and generally associated with a favorable prognosis. In contrast, Type II tumors are largely estrogen-independent, characterized by high-grade histology, less frequent occurrence, and a comparatively poor clinical outcome (236). In women with endometrial cancer, alterations in the vaginal microbiota have been observed, characterized by the presence of specific bacterial taxa, including Firmicutes, Spirochaetes, Actinobacteria (e.g., Atopobium), and Proteobacteria (e.g., Bacteroides and Porphyromonas), often accompanied by an elevated vaginal pH (237). Notably, Atopobium and Porphyromonas have been shown to stimulate the release of proinflammatory cytokines, including IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-17α, and TNF-α (238).

Ovarian cancer (OC) represents the second most prevalent malignancy of the female reproductive system, following endometrial cancer, and predominantly arises in postmenopausal women. The disease primarily affects individuals aged 55-70 years, with incidence peaking between ages 55 and 59. Alarmingly, approximately 70% of ovarian cancer cases are diagnosed at advanced stages (FIGO stages III-IV), reflecting the insidious onset and lack of specific early clinical manifestations (239). Emerging evidence indicates a potential link between the gut microbiota and ovarian cancer. The gut microbial community has been shown to influence systemic inflammatory processes and modulate host immune responses, thereby shaping the ovarian tumor microenvironment and potentially contributing to disease initiation and progression (240). Microbiome diversity and richness within OC niches are markedly reduced, with certain taxa exhibiting relative enrichment compared to non-cancerous tissues (241-243). Notably, Propionibacterium acnes, Acetobacter, members of the phyla Firmicutes, Proteobacteria, and Fusobacterium demonstrate increased abundance, whereas Lactococcus is significantly diminished (159, 241-245). Several of these bacteria have been implicated in shaping a pro-tumorigenic inflammatory microenvironment by activating inflammatory signaling cascades and oxidative stress responses. By isolating and culturing specific strains, Huang et al. confirmed the overrepresentation of these genera and identified P. acnes as the predominant strain in OC. Functional assays further demonstrated its tumor-promoting role in epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC), wherein P. acnes activates the Hedgehog pathway and elevates proinflammatory mediators, including TNF-α and IL-1β (246). Additionally, iron-induced oxidative stress mediated by Acetobacter and Lactobacillus in clear-cell OC drives persistent inflammation, DNA damage, and oncogene activation, ultimately fostering tumor progression (247). However, whether these microbial effects are sufficient to initiate tumorigenesis or merely accelerate preexisting oncogenic processes remains a matter of debate. Notably, conflicting data exist regarding whether microbial-derived metabolites act as tumor suppressors or promoters, highlighting the context-dependent nature of host-microbiome interactions. The relationship between cancer and microorganisms, as described above, is illustrated in the figure below (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Microbiome signatures and clinical implications across major cancer types. The figure integrates distinct microbial taxa or communities associated with individual malignancies. Colored nodes denote microbial taxa enriched in specific tumors, while connecting lines represent shared or overlapping microbial associations. Icons indicate key biological effects, including inflammation, metabolic alteration, immune modulation, or direct oncogenic activity. This integrative framework highlights the potential of microbial profiles as diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic biomarkers across diverse cancer types.

3. Microbiome and Cancer Therapy

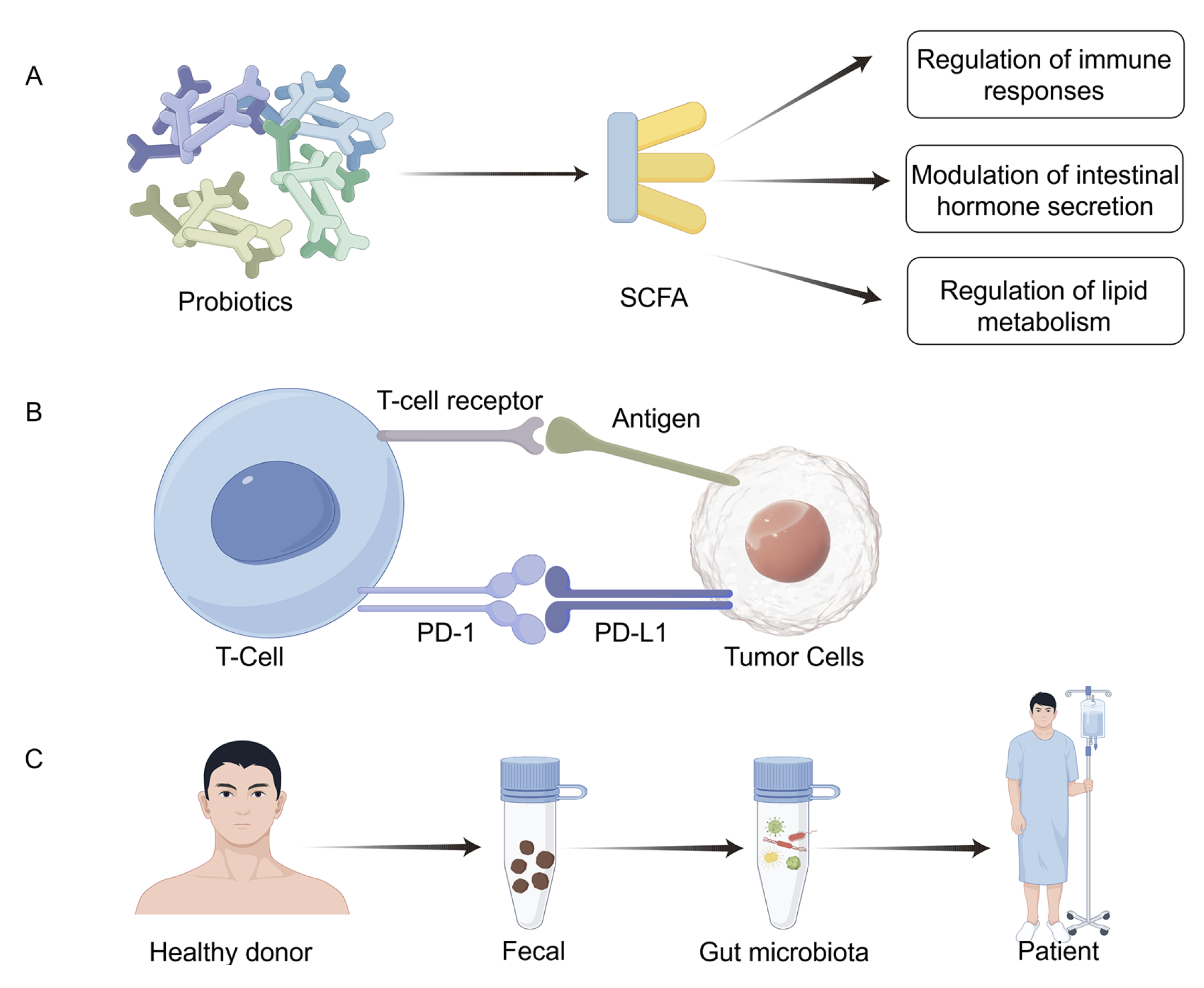

Probiotics are defined as live microorganisms that, when administered in sufficient amounts, confer health benefits to the host (248). They are widely used as standardized dietary supplements and are generally recognized as safe (249). A major mechanism through which probiotics exert beneficial effects is the production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), particularly butyrate, generated by the fermentation of polysaccharides by species such as Clostridium butyricum and Akkermansia muciniphila (250). Butyrate has pleiotropic roles, including regulation of immune responses, modulation of intestinal hormone secretion, and regulation of lipid metabolism. For example, butyrate has been shown to induce apoptosis in colon cancer cell lines, suppressing tumor cell growth by upregulating the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p57, thereby contributing to cell cycle arrest and tumor suppression (251). Prebiotics are defined as selectively fermented, non-digestible dietary fibers that promote the growth and activity of probiotic microorganisms. By maintaining intestinal microbial homeostasis and mitigating gut dysbiosis, prebiotics play a significant role in promoting host health. Their primary site of action is the colon, where they modulate resident populations of Lactobacilli and Bifidobacteria, thereby enhancing SCFA production. These SCFAs exert diverse physiological effects, including reinforcement of the gut epithelial and mucus barriers, regulation of immune responses, modulation of glucose and lipid metabolism, and influence on energy expenditure and satiety (252).

Beyond their local effects on epithelial integrity, SCFAs, notably acetate, propionate, and butyrate, play essential roles in systemic immune regulation and metabolic reprogramming. Butyrate acts as a histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor, promoting the differentiation of regulatory T cells (Tregs) through enhanced FOXP3 expression and suppressing pro-inflammatory Th17 responses (253). SCFAs also regulate macrophage polarization, shifting M1-like inflammatory phenotypes toward M2-like, anti-inflammatory states via G-protein-coupled receptors (GPR41, GPR43) and downstream AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) signaling. Furthermore, by serving as energy substrates in colonocytes and tumor-associated immune cells, SCFAs influence metabolic rewiring, including modulation of glycolysis and fatty acid oxidation. Bile acids (BAs), another major class of microbiota-derived metabolites, exert equally profound effects on tumor biology. Primary BAs synthesized in the liver are converted into secondary BAs such as deoxycholic acid (DCA) and lithocholic acid (LCA) by intestinal bacteria (253). Collectively, SCFAs and BAs exemplify how microbial metabolites link gut microbial ecology with host immune-metabolic networks, influencing both tumor initiation and therapeutic response.

The immune system plays a central role in tumor surveillance and suppression, and strategies that harness its activity have become pivotal in cancer therapy. Among these, immunotherapy has emerged as a transformative treatment modality across diverse malignancies. In particular, immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) has gained prominence, employing monoclonal antibodies that target inhibitory pathways, such as programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1), its ligand PD-L1, and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4). By releasing the brakes on T-cell activation, these agents enhance antitumor immune responses and have demonstrated durable clinical benefits in subsets of patients (254). Hua D et al. demonstrated that anti-PD-L1 therapy, when combined with Clostridium butyricum (CB) and Akkermansia muciniphila (AKK), markedly suppressed colitis-associated colorectal cancer (CRC) progression. This combination not only attenuated excessive activation of CD8⁺ T cells and macrophages within the inflammatory milieu but also enhanced CRC cell responsiveness to anti-PD-L1 treatment. Collectively, these findings suggest that CB and AKK exert direct antitumor effects, thereby improving the efficacy of immune checkpoint blockade and providing a promising therapeutic approach (255). Specific commensals, such as Bifidobacterium and Akkermansia muciniphila, enhance anti-PD-(L)1 or anti-CTLA-4 responses by activating dendritic cells, improving antigen presentation, and promoting the infiltration of cytotoxic CD8⁺ T cells into tumors. In contrast, broad-spectrum antibiotics or germ-free conditions markedly reduce ICI efficacy and alter the tumor immune microenvironment toward an immunosuppressive phenotype (Table 5).

Table 5. Representative studies on microbiome-ICI interactions.

| Study type | Cancer type |

Intervention/ Exposure |

Microbiome features | Immune effects | Clinical outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preclinical | Melanoma (mouse) |

Bifidobacterium + anti-PD-L1 |

↑ DC activation, ↑ CD8⁺ T-cell infiltration |

↑ IFN-γ response | Enhanced tumor control |

| Preclinical | Multiple (mouse) | Broad-spectrum antibiotics before ICI | ↓ Microbial diversity | ↓ Antigen presentation, ↑ MDSCs | Reduced ICI efficacy |

| Observational | Melanoma/Lung/RCC | Baseline gut microbiome | ↑ Akkermansia, Faecalibacterium | ↑ Th1/CTL signatures | Improved ORR/PFS/OS |

| Interventional | Melanoma (phase I) |

FMT from responders + anti-PD-1 |

Microbiome shifted to responder-like pattern | ↑ T-cell activation | Partial responses in resistant |